I received some exciting news last week: I've been appointed to the Notable Children's Recordings Committee for the next two years. This is, in many ways, the perfect appointment for me. I prefer chummy "best of" lists to "there can be only one" awards, and I'm a total audiobook fiend. I keep having to upgrade my Audible account.

This does, however, mean that I won't be able to help Sam write this blog next year. If you would like to take pity on him and offer to write a guest post or two, I think he's more than open to the idea!

I don't think I'll be blogging about audiobooks next year, but I may change my mind. I will be writing them up over on Goodreads, though.

Friday, December 20, 2013

2014 Contenders: Counting by 7s, by Holly Goldberg Sloan

Counting by 7s is the story of Willow Chance, a precocious 12-year-old whose parents are killed in an automobile accident. It details the aftermath of this tragedy, and Willow's attempts to build a new life and a new home with a cast of other people who don't quite fit in.

The book is getting a fair amount of awards buzz, and a lot of reviewers have really positive things to say about it. Having finished it, however, I find myself unpersuaded.

The biggest problem I had is with Willow herself. I didn't believe in her for a second -- she reads like the kind of genius you see on a TV show rather than one you might actually encounter in real life. She effortlessly learns and recalls information about gardening, zoology, epidemiology, dermatology, beekeeping, astrophysics, computer hardware, legal agreements, spatial design, astronomy, network hacking, modernist poetry, and multiple foreign languages (Spanish, Latin, Vietnamese), to the point that even Marilyn Vos Savant might be hard-pressed to keep up. She aces a test that apparently not a single other child in the state of California has gotten perfect, and yet she hasn't so much as skipped a grade. As middle school prodigies go, she's slightly less realistic than Susan and Mary Test, and significantly more problematic than Early Auden, whom I've already complained about at length.

That might work if it were played for laughs, or if it were in some kind of larger-than-life tall tale, but Counting by 7s is ostensibly contemporary fiction with no fantastic elements. Willow's character kept jarring me out of that world with her impossibility.

This is even more true because the facts in the book have moments where they veer away from the truth significantly. Willow has a story she tells (and references repeatedly) about the flock of green-rumped parrots that lived by her house. However, the book is set in Bakersfield, California, and according to the Official California Bird Records, there has never been a recorded sighting of a green-rumped parrot (or parrotlet, which is what it's usually called) in California, much less a flock of them moving into someone's backyard. If she's an expert in zoology at the level at which she is presented -- and, especially since the book shifts constantly between first and third person narration, there's no reason to view Willow as an unreliable narrator -- that seems like the sort of mistake she wouldn't make.

Counting by 7s has a heartwarming plot, and the sentence-level writing is quite good, if presented in a somewhat stilted cadence. But, in the end, I'm not convinced about this one at all.

Published in August by Dial Books for Young Readers

The book is getting a fair amount of awards buzz, and a lot of reviewers have really positive things to say about it. Having finished it, however, I find myself unpersuaded.

The biggest problem I had is with Willow herself. I didn't believe in her for a second -- she reads like the kind of genius you see on a TV show rather than one you might actually encounter in real life. She effortlessly learns and recalls information about gardening, zoology, epidemiology, dermatology, beekeeping, astrophysics, computer hardware, legal agreements, spatial design, astronomy, network hacking, modernist poetry, and multiple foreign languages (Spanish, Latin, Vietnamese), to the point that even Marilyn Vos Savant might be hard-pressed to keep up. She aces a test that apparently not a single other child in the state of California has gotten perfect, and yet she hasn't so much as skipped a grade. As middle school prodigies go, she's slightly less realistic than Susan and Mary Test, and significantly more problematic than Early Auden, whom I've already complained about at length.

That might work if it were played for laughs, or if it were in some kind of larger-than-life tall tale, but Counting by 7s is ostensibly contemporary fiction with no fantastic elements. Willow's character kept jarring me out of that world with her impossibility.

This is even more true because the facts in the book have moments where they veer away from the truth significantly. Willow has a story she tells (and references repeatedly) about the flock of green-rumped parrots that lived by her house. However, the book is set in Bakersfield, California, and according to the Official California Bird Records, there has never been a recorded sighting of a green-rumped parrot (or parrotlet, which is what it's usually called) in California, much less a flock of them moving into someone's backyard. If she's an expert in zoology at the level at which she is presented -- and, especially since the book shifts constantly between first and third person narration, there's no reason to view Willow as an unreliable narrator -- that seems like the sort of mistake she wouldn't make.

Counting by 7s has a heartwarming plot, and the sentence-level writing is quite good, if presented in a somewhat stilted cadence. But, in the end, I'm not convinced about this one at all.

Published in August by Dial Books for Young Readers

Wednesday, December 11, 2013

2014 Contenders: Salt, by Helen Frost

Whenever I pick up a verse novel, the first thing that goes through my head is the question, "why this story in this format?" That is, what is it about this story or these characters that makes the author feel like verse would work better than prose to communicate the narrative?

Sometimes, there's a good answer. In The Wild Book, the narrator has tried writing in poetry as a way to help her dyslexia. In The One and Only Ivan (which, while not a full-on verse novel, has certain verse novel elements), the clipped, understated narration is meant to help show what it's like inside a gorilla's head.

More often, however, I can't find an answer that satisfies me. And that was probably my biggest complaint about Salt -- that I was never able to answer that question to my satisfaction. True, it allows for the book to switch quickly between its protagonists, but that's something that can be done in pure prose form too, and I think it might have benefited from that approach.

I also felt like the brief nature of all the scenes meant that the characterization wasn't particularly deep. We get a fairly good feel for James and Anikwa, the narrators, but the secondary characters end up painted in very broad strokes. Even with James and Anikwa, I felt like the characterization didn't have enough nuance for their conflict halfway through the book to really feel natural.

A lot of the language is beautiful -- anyone who loved Step Gently Out last year knows that Helen Frost is highly skilled with imagery. I'm not sure I felt like all the line breaks were purposeful enough, however, and I don't think that giving all of Anikwa's poems a specific shape on the page (one that's sort of like three stacked balls) helped with that challenge.

I did enjoy the setting -- the war of 1812 isn't a popular choice for children's books, and the portion of the conflict that didn't take place around the Chesapeake Bay even less so. I did feel like I'd spent some time in an interesting place after I'd finished the book.

The setting, however, was the only facet of the book that I felt was truly distinguished. That might be enough to get Salt on the notables list, but I'd be very surprised if it showed up in the Newbery announcement.

Published in July by Farrar Straus Giroux

Sometimes, there's a good answer. In The Wild Book, the narrator has tried writing in poetry as a way to help her dyslexia. In The One and Only Ivan (which, while not a full-on verse novel, has certain verse novel elements), the clipped, understated narration is meant to help show what it's like inside a gorilla's head.

More often, however, I can't find an answer that satisfies me. And that was probably my biggest complaint about Salt -- that I was never able to answer that question to my satisfaction. True, it allows for the book to switch quickly between its protagonists, but that's something that can be done in pure prose form too, and I think it might have benefited from that approach.

I also felt like the brief nature of all the scenes meant that the characterization wasn't particularly deep. We get a fairly good feel for James and Anikwa, the narrators, but the secondary characters end up painted in very broad strokes. Even with James and Anikwa, I felt like the characterization didn't have enough nuance for their conflict halfway through the book to really feel natural.

A lot of the language is beautiful -- anyone who loved Step Gently Out last year knows that Helen Frost is highly skilled with imagery. I'm not sure I felt like all the line breaks were purposeful enough, however, and I don't think that giving all of Anikwa's poems a specific shape on the page (one that's sort of like three stacked balls) helped with that challenge.

I did enjoy the setting -- the war of 1812 isn't a popular choice for children's books, and the portion of the conflict that didn't take place around the Chesapeake Bay even less so. I did feel like I'd spent some time in an interesting place after I'd finished the book.

The setting, however, was the only facet of the book that I felt was truly distinguished. That might be enough to get Salt on the notables list, but I'd be very surprised if it showed up in the Newbery announcement.

Published in July by Farrar Straus Giroux

Friday, December 6, 2013

2014 Contenders: Locomotive, by Brian Floca

Locomotive is another of our Morris Seminar books, and a very good one it is, too. It's by Brian Floca, who has already won two Sibert Honors as author and illustrator of Lightship (2008) and Moonshot (2010), as well as a third for his illustrations for Jan Greenberg and Sandra Johnson's Ballet for Martha (2011). His fascination with transportation continues here, in an evocative free-verse description of a trans-continental railway journey as it was in 1869.

As we've been mentioning in recent days, the strongest nonfiction of the year seems (in our collective opinion) to be concentrated in the picture book section. Locomotive is another title that deserves to be in the mix with Brave Girl, A Splash of Red, and On a Beam of Light. Interestingly, however, I think it's not as good a Newbery candidate as some of the others, because of the relationship between the text and the illustrations.

One of the ways that Floca creates continuity in Locomotive is by putting words that describe sounds in markedly different fonts from the rest of the text. This works beautifully in the context of the book as a whole, but it's a strategy that's more design than pure text. Much the same could be said of Floca's choice to put some of the lines uttered by the railway workers in speech bubbles. The line between text and illustrations gets very blurry in Locomotive, and although that's fine for the Sibert, it makes Newbery consideration highly problematic.

As a book, I like On a Beam of Light a little better than Locomotive, but I recognize that that's essentially an issue of personal taste -- I like science-y subjects, and I prefer Jennifer Berne's understated prose to Floca's whooshing, onomatopoetic poetry -- rather than any kind of pure critical judgement. However, I think On a Beam of Light does objectively fit the Newbery criteria better, mostly because there's simply more left once one removes the illustrations from consideration.

In reality, the Newbery is probably a pipe dream for both books. However, I'm starting to get really, really curious about this year's Sibert results, where Locomotive could easily carry the day.

Published in September by Atheneum.

As we've been mentioning in recent days, the strongest nonfiction of the year seems (in our collective opinion) to be concentrated in the picture book section. Locomotive is another title that deserves to be in the mix with Brave Girl, A Splash of Red, and On a Beam of Light. Interestingly, however, I think it's not as good a Newbery candidate as some of the others, because of the relationship between the text and the illustrations.

One of the ways that Floca creates continuity in Locomotive is by putting words that describe sounds in markedly different fonts from the rest of the text. This works beautifully in the context of the book as a whole, but it's a strategy that's more design than pure text. Much the same could be said of Floca's choice to put some of the lines uttered by the railway workers in speech bubbles. The line between text and illustrations gets very blurry in Locomotive, and although that's fine for the Sibert, it makes Newbery consideration highly problematic.

As a book, I like On a Beam of Light a little better than Locomotive, but I recognize that that's essentially an issue of personal taste -- I like science-y subjects, and I prefer Jennifer Berne's understated prose to Floca's whooshing, onomatopoetic poetry -- rather than any kind of pure critical judgement. However, I think On a Beam of Light does objectively fit the Newbery criteria better, mostly because there's simply more left once one removes the illustrations from consideration.

In reality, the Newbery is probably a pipe dream for both books. However, I'm starting to get really, really curious about this year's Sibert results, where Locomotive could easily carry the day.

Published in September by Atheneum.

Thursday, December 5, 2013

2014 Contenders: Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans during World War II, by Martin W. Sandler

This is a solid book about a topic that's seldom given the attention it deserves: the imprisonment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. If I were reviewing it in detail, I would pay close attention to the way it's organized, indexed, etc.

I am not reviewing it in detail. I have been out of the office (traveling, dealing with my sickness, and then dealing with my kid's sickness) for a week and a half. I have Sam's permission to write a Short Grouchy Review (patent pending) of this one. In fact, I am going to deploy bullet points.

Neither of them are going to win the Newbery, and, as Sam mentioned today, I'm kind of hoping that the Sibert goes to a nonfiction picture book this year. Brave Girl and A Splash of Red are both great choices, Sam loved On a Beam of Light, and I haven't been able to get my hands on The Mad Potter yet, but I'm a big fan of any Greenberg/Jordan collaboration.

Published in May by Walker Childrens

I am not reviewing it in detail. I have been out of the office (traveling, dealing with my sickness, and then dealing with my kid's sickness) for a week and a half. I have Sam's permission to write a Short Grouchy Review (patent pending) of this one. In fact, I am going to deploy bullet points.

- The prose is adequate, but that's all. I noted that the prose in Courage Has No Color was not up to Tanya Lee Stone's usual standard, but it's still noticeably better than the prose in this book.

- I mentally took away organization points for the ineffective way the full-spread sidebars were integrated into the text. I hate when I have to stop mid-sentence and decide whether to read a sidebar or mark it with my thumb and return to it later.

- Content-wise, it was quite comprehensive, giving ample attention to the historical background (Japanese immigration and resulting persecution) and the redress movement and ongoing ramifications. The link to 9/11 and persecution of American Muslims and Sikhs was especially welcome.

Neither of them are going to win the Newbery, and, as Sam mentioned today, I'm kind of hoping that the Sibert goes to a nonfiction picture book this year. Brave Girl and A Splash of Red are both great choices, Sam loved On a Beam of Light, and I haven't been able to get my hands on The Mad Potter yet, but I'm a big fan of any Greenberg/Jordan collaboration.

Published in May by Walker Childrens

2014 Contenders: On a Beam of Light, by Jennifer Berne

Here it is -- the one that I feel is unequivocally the best nonfiction title of the year, the one that can stand with last year's best efforts, and that I'd love to see receive some serious Newbery discussion.

That last part isn't likely to happen, alas, because On a Beam of Light is not only a nonfiction title, but a picture book as well. Yet the book takes the life of Albert Einstein, a figure whose achievements aren't all that easy to explain to a child, and uses them as a framework for some of the most perceptive prose of the year. My favorite passage is on the page from which the book takes its title:

"And in his mind, right then and there, Albert was no longer on his bicycle, no longer on the country road...he was racing through space on a beam of light."

Reading lines like that, I'm on that beam of light as well.

It's not, of course, relevant to the Newbery discussion, but the illustrations by Vladimir Radunsky are the perfect counterpoint to the text, full of whimsy, poignance, and huge washes of negative space. That sort of thing is relevant to the Sibert committee, however, and Rachael and I were wondering today if this might indeed be a year when the Sibert winner is drawn from the ranks of the picture book nonfiction (as in 2012, when Balloons Over Broadway took the medal).

On a Beam of Light is one of our discussion titles for the Morris Seminar in January, and I can't wait to see what the other participants think of it. I also can't wait to talk about how much I love it!

Published in April by Chronicle Books

That last part isn't likely to happen, alas, because On a Beam of Light is not only a nonfiction title, but a picture book as well. Yet the book takes the life of Albert Einstein, a figure whose achievements aren't all that easy to explain to a child, and uses them as a framework for some of the most perceptive prose of the year. My favorite passage is on the page from which the book takes its title:

"And in his mind, right then and there, Albert was no longer on his bicycle, no longer on the country road...he was racing through space on a beam of light."

Reading lines like that, I'm on that beam of light as well.

It's not, of course, relevant to the Newbery discussion, but the illustrations by Vladimir Radunsky are the perfect counterpoint to the text, full of whimsy, poignance, and huge washes of negative space. That sort of thing is relevant to the Sibert committee, however, and Rachael and I were wondering today if this might indeed be a year when the Sibert winner is drawn from the ranks of the picture book nonfiction (as in 2012, when Balloons Over Broadway took the medal).

On a Beam of Light is one of our discussion titles for the Morris Seminar in January, and I can't wait to see what the other participants think of it. I also can't wait to talk about how much I love it!

Published in April by Chronicle Books

Wednesday, December 4, 2013

2014 Contenders: The Tapir Scientist, by Sy Montgomery

How do you go about studying an animal that a) is critical to the health of its environment, but b) is shy, nocturnal, and lives in a snarl of tangled bushes, omnipresent mosquitoes and ticks, and suffocating heat and humidity? In The Tapir Scientist, Sy Montgomery and photographer Nic Bishop get to find out firsthand, as they accompany biologist Pati Medici and her team out into the field to study the elusive tapir, the largest mammal native to South America.

As an informational text, The Tapir Scientist generally succeeds. It does a great job of showing what life on a field expedition is like: the tedium, the difficult working conditions, the disappointments -- and then the thrill of encountering a majestic animal face to face, and learning information that could help ensure its survival. It also details the place of the tapir in its natural ecosystem, and explains how the lives of the animals intersect with the people who live in the same place. Sy Montgomery is always good for an above-average book -- we loved her Temple Grandin last year -- and The Tapir Scientist certainly is that.

It's instructive, however, to compare The Tapir Scientist with something like Moonbird, another book featuring an author working with scientists in the field. In Moonbird, Phillip Hoose turned the story of a bird into a rumination on the relationship between the human and natural worlds, both honoring and transcending his ostensible subject. I don't think The Tapir Scientist achieves that level of sophistication and depth, or even really approaches it.

I'm also not entirely sold on the design of the book. Nic Bishop is a first-class photographer, and his images are excellent; I think they're often not placed in the best position respective to the text, however. The font choice also seems odd -- I had to stare at the sidebar-style sections for a while to convince myself that they weren't actually printed in Comic Sans, just something uncomfortably reminiscent of it -- and, although most of the important words are defined in the text, there's no end glossary.

In the end, The Tapir Scientist is absolutely a recommend-for-purchase title, at least in this one man's opinion. I don't expect any Sibert love for it, however, and I don't think the Newbery committee will be at all swayed in the book's direction.

Published in July by Houghton Mifflin Books for Children

As an informational text, The Tapir Scientist generally succeeds. It does a great job of showing what life on a field expedition is like: the tedium, the difficult working conditions, the disappointments -- and then the thrill of encountering a majestic animal face to face, and learning information that could help ensure its survival. It also details the place of the tapir in its natural ecosystem, and explains how the lives of the animals intersect with the people who live in the same place. Sy Montgomery is always good for an above-average book -- we loved her Temple Grandin last year -- and The Tapir Scientist certainly is that.

It's instructive, however, to compare The Tapir Scientist with something like Moonbird, another book featuring an author working with scientists in the field. In Moonbird, Phillip Hoose turned the story of a bird into a rumination on the relationship between the human and natural worlds, both honoring and transcending his ostensible subject. I don't think The Tapir Scientist achieves that level of sophistication and depth, or even really approaches it.

I'm also not entirely sold on the design of the book. Nic Bishop is a first-class photographer, and his images are excellent; I think they're often not placed in the best position respective to the text, however. The font choice also seems odd -- I had to stare at the sidebar-style sections for a while to convince myself that they weren't actually printed in Comic Sans, just something uncomfortably reminiscent of it -- and, although most of the important words are defined in the text, there's no end glossary.

In the end, The Tapir Scientist is absolutely a recommend-for-purchase title, at least in this one man's opinion. I don't expect any Sibert love for it, however, and I don't think the Newbery committee will be at all swayed in the book's direction.

Published in July by Houghton Mifflin Books for Children

Friday, November 22, 2013

2014 Contenders: If You Want to See a Whale, by Julie Fogliano

Every year, a picture book or two gets bandied about in the (online, publicly visible) Newbery discussions. Last year gave us Each Kindness and Step Gently Out. This year, we've had Africa Is My Home (assuming you take it as a picture book, rather than a heavily-illustrated work of short fiction); the other title that I've seen crop up in the most discussions is probably If You Want to See a Whale.

In a way, it's academic exercise, discussing these picture books. No "traditional" picture book has ever won the Newbery (though that's an assertion that assumes you agree with me on how to categorize A Visit to William Blake's Inn [1982 winner], which I think of as an illustrated collection of poetry rather than a picture book, and which is filed in the 811s in our local library system, but which did win a Caldecott Honor). The Honors list isn't much better -- aside from another poetry book, Dark Emperor (2011 Honor), the only picture books I can find are Wanda Gág's Millions of Cats (1929 Honor) and The ABC Bunny (1934 Honor), from the pre-Caldecott days. (If you can think of one I missed, leave a comment!)

And yet I feel like it's an important discussion to continue having. Even without the iconic illustrations, the texts of Goodnight Moon and Where the Wild Things Are and Horton Hears a Who are, I would argue, key parts of American children's literature. It's very hard to talk about picture books without considering the illustrations -- it feels kind of like trying to evaluate a symphony without ever mentioning the string section -- but the ones that fall within the Newbery range (which is the overwhelming majority of them) deserve our attention nonetheless.

With all that said, it seems to me that the text of If You Want to See a Whale does several things extremely well, and a few things maybe not as well. The sound of the book when read aloud is fantastic -- Julie Fogliano has a keen ear for alliteration and assonance, and lines such as the ones in which she describes clouds "in the sky that's spread out, side to side" are a joy just to say. The ending of the book in the text is also beautifully ambiguous, fading out on the lines "and wait... / and wait... / and wait..." The last of illustrator Erin E. Stead's pictures shows the whale quest coming to a successful end, but it does so wordlessly -- although she's given us a tidy ending, Fogliano as author has declined to do so.

The main thing that bothered me -- and maybe it's just from sitting through too many Creative Writing workshops back in college -- was the book's unwillingness to fully commit to its central conceit. I know that the book isn't really about whale-watching at all, but a metaphor is best when it works on both the literal and figurative levels. A window isn't helpful for watching for whales (or at least, nowhere near as helpful as being outside), and if you're on a beach or in a boat, roses and bugs aren't likely distractions.

This doesn't mean that If You Want to See a Whale isn't a delight, but I do think it means that it's not Newbery material. When Rachael reviewed Each Kindness last year, she talked about the intense difficulty of writing a short text. One flawed line in a 300-page novel might pass by unnoticed; the same isn't true of a poem of 52 lines, several of which are only two or three words long. Surviving the scrutiny that such a short text invites is an incredibly high bar, and I'm unconvinced that Whale clears it.

Published in May by Roaring Book Press

In a way, it's academic exercise, discussing these picture books. No "traditional" picture book has ever won the Newbery (though that's an assertion that assumes you agree with me on how to categorize A Visit to William Blake's Inn [1982 winner], which I think of as an illustrated collection of poetry rather than a picture book, and which is filed in the 811s in our local library system, but which did win a Caldecott Honor). The Honors list isn't much better -- aside from another poetry book, Dark Emperor (2011 Honor), the only picture books I can find are Wanda Gág's Millions of Cats (1929 Honor) and The ABC Bunny (1934 Honor), from the pre-Caldecott days. (If you can think of one I missed, leave a comment!)

And yet I feel like it's an important discussion to continue having. Even without the iconic illustrations, the texts of Goodnight Moon and Where the Wild Things Are and Horton Hears a Who are, I would argue, key parts of American children's literature. It's very hard to talk about picture books without considering the illustrations -- it feels kind of like trying to evaluate a symphony without ever mentioning the string section -- but the ones that fall within the Newbery range (which is the overwhelming majority of them) deserve our attention nonetheless.

With all that said, it seems to me that the text of If You Want to See a Whale does several things extremely well, and a few things maybe not as well. The sound of the book when read aloud is fantastic -- Julie Fogliano has a keen ear for alliteration and assonance, and lines such as the ones in which she describes clouds "in the sky that's spread out, side to side" are a joy just to say. The ending of the book in the text is also beautifully ambiguous, fading out on the lines "and wait... / and wait... / and wait..." The last of illustrator Erin E. Stead's pictures shows the whale quest coming to a successful end, but it does so wordlessly -- although she's given us a tidy ending, Fogliano as author has declined to do so.

The main thing that bothered me -- and maybe it's just from sitting through too many Creative Writing workshops back in college -- was the book's unwillingness to fully commit to its central conceit. I know that the book isn't really about whale-watching at all, but a metaphor is best when it works on both the literal and figurative levels. A window isn't helpful for watching for whales (or at least, nowhere near as helpful as being outside), and if you're on a beach or in a boat, roses and bugs aren't likely distractions.

This doesn't mean that If You Want to See a Whale isn't a delight, but I do think it means that it's not Newbery material. When Rachael reviewed Each Kindness last year, she talked about the intense difficulty of writing a short text. One flawed line in a 300-page novel might pass by unnoticed; the same isn't true of a poem of 52 lines, several of which are only two or three words long. Surviving the scrutiny that such a short text invites is an incredibly high bar, and I'm unconvinced that Whale clears it.

Published in May by Roaring Book Press

Thursday, November 21, 2013

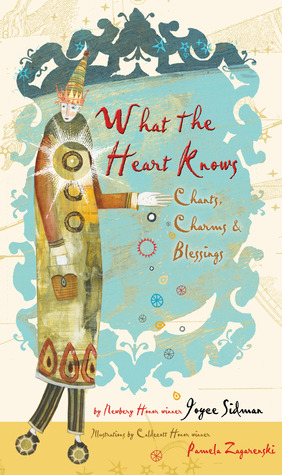

2014 Contenders: What the Heart Knows, by Joyce Sidman

Joyce Sidman's newest book of poetry is a strange beast indeed. The subtitle is "Chants, Charms & Blessings," and in her note to readers, Sidman talks about how humans have always "used language to try to influence the world," and encourages readers to make poems of their own and "chant them, in your own voice." She divides her book into four parts: Chants & Charms, Spells & Invocations, Laments & Remembrances, and Praise Songs & Blessings. The result is something like a poetic Book of Common Prayer (or Book of Shadows), with all of the elevated diction and heightened emotion such a mode requires. Both the subject matter and tone are widely varied among the individual poems, soaring from lost socks to the slippery nature of time, and then swooping back down to ugly sweaters, all the in the space of three pages.

Joyce Sidman's newest book of poetry is a strange beast indeed. The subtitle is "Chants, Charms & Blessings," and in her note to readers, Sidman talks about how humans have always "used language to try to influence the world," and encourages readers to make poems of their own and "chant them, in your own voice." She divides her book into four parts: Chants & Charms, Spells & Invocations, Laments & Remembrances, and Praise Songs & Blessings. The result is something like a poetic Book of Common Prayer (or Book of Shadows), with all of the elevated diction and heightened emotion such a mode requires. Both the subject matter and tone are widely varied among the individual poems, soaring from lost socks to the slippery nature of time, and then swooping back down to ugly sweaters, all the in the space of three pages.I don't believe I've ever had cause to mention my religious background on this blog, or in any of my writing about children's books. In the interest of making clear the kind of reader I am, though, I think it's only fair to say that I have been a solitary Pagan, a high church Episcopalian, an enthusiastic half-Jew, a Unitarian-Universalist, and a quasi-Buddhist in my life. Like the titular character in Life of Pi, I'm spiritually profligate - I just love a good prayer. And even outside of overt spirituality, I've built my entire life around the idea that words can shape reality. This book basically speaks directly to my heart.

Even as a biased reader, though, I think it's fair to say that this is a magnificent collection of poetry. Sidman is the Kevin Henkes of children's poets: I don't know any serious children's poet who speaks so respectfully to their readers. The best poetry is always about more than what it's about, and Sidman achieves that more often than not in this collection, turning ordinary objects into metaphors for loss, transience, and comfort. She does not restrict herself to the tangible, though - occasionally the poems enter the realm of pure surrealism, as in "Song in a Strange Land," which plays out like a fever dream.

What the Heart Knows is not only distinguished thematically, though. The poems are also characterized by razor-sharp imagery, as in "Blessing on the Smell of Dog": "May his scent seep through / perfumed shampoos / like the rich tang of mud in spring." The sound of the words themselves is deeply satisfying as well, filled with the repetition, alliteration, and insistent rhythms that characterize the tradition of sacred poetry. The fact that these are secular prayers only adds to their power, solemnizing the topics we usually dismiss.

Other reviewers have pointed out that the poems are not perfectly equal in quality, and that's fair, but there's very little filler, in my opinion. Nina also questioned whether the illustrations distract from the poetry, and I think that is actually a good question - I was so focused on the text that I barely noticed the illustrations at all. It's possible that the book would be even more effective with a simpler design. There is the age question as well - this is really aimed higher than Sidman's usual middle-grade age range, but surely not too high for the Newbery.

Overall, it's a gorgeous piece of work - definitely in my top five books of the year - and I do hope it gets some love on Newbery day.

Published in October by HMH Books for Young Readers

The Ones We're About to Mock

Oo-de-lally! Sam and I have settled on a final reading list for the

Maryland Mock Newbery (to take place on January 6 at the Caroline

County Public Library - register at the Maryland Library Association website, email any questions to Rachael, etc., etc.)!

For those who wish to mock with us, please to be seeking these titles:

1. Doll Bones, by Holly Black

2. Zebra Forest, by Adina Rishe Gewirtz

3. The Center of Everything, by Linda Urban

4. The Real Boy, by Anne Ursu

5. P.S. Be Eleven, by Rita Williams-Garcia

PLUS

6. Penny and Her Marble, by Kevin Henkes

I know. We snuck in a sixth book that wasn't even on the semifinal list.

As always, we hope that these books represent a variety of genres and styles that will make for a lively discussion in January - though not as much variety as we would like, because we didn't feel that any of the nonfiction this year could go toe to toe with the best fiction. And I would have loved to include some poetry - namely, What the Heart Knows, by Joyce Sidman.

Actually, there are a lot of books we would have loved to include but couldn't or didn't. I'm second-guessing my choice not to put Better Nate Than Ever on my semi-final list, and Sam wishes he'd included The Hidden Summer. And then there's Far, Far Away, probably my favorite book of the year, but one I read too late to add it to my list.

Since we are but a mock committee, though, our humble six will have to do, and I think they will do quite nicely. Happy reading!

For those who wish to mock with us, please to be seeking these titles:

1. Doll Bones, by Holly Black

2. Zebra Forest, by Adina Rishe Gewirtz

3. The Center of Everything, by Linda Urban

4. The Real Boy, by Anne Ursu

5. P.S. Be Eleven, by Rita Williams-Garcia

PLUS

6. Penny and Her Marble, by Kevin Henkes

I know. We snuck in a sixth book that wasn't even on the semifinal list.

As always, we hope that these books represent a variety of genres and styles that will make for a lively discussion in January - though not as much variety as we would like, because we didn't feel that any of the nonfiction this year could go toe to toe with the best fiction. And I would have loved to include some poetry - namely, What the Heart Knows, by Joyce Sidman.

Actually, there are a lot of books we would have loved to include but couldn't or didn't. I'm second-guessing my choice not to put Better Nate Than Ever on my semi-final list, and Sam wishes he'd included The Hidden Summer. And then there's Far, Far Away, probably my favorite book of the year, but one I read too late to add it to my list.

Since we are but a mock committee, though, our humble six will have to do, and I think they will do quite nicely. Happy reading!

2014 Second Takes: Doll Bones, by Holly Black

Maybe ten years ago, I checked a book out of the library at the University of Houston. It was a 1958 monograph called An Investigation of Gondal, and it was an attempt by scholar William Doremus Paden to reconstruct a fictional world created and played as a sort of game by Emily and Anne Brontë. Although the sisters were teenagers when they started developing that particular world, they continued to play their game with it well into adulthood, maybe even until they died. It's the setting of some of Emily's best poetry, and the sisters even produced a prose work called The Gondal Chronicles, though that piece was never published and is now lost.

Though no child reader would be likely to know of it, Gondal is very much like "The Game" that the main characters in Doll Bones play. At least the earliest stages of the Brontës' game involved toy soldiers (which The Game also includes, along with other dolls and figures), and, like the Brontës, Poppy, Zach, and Alice produce writing about their fictional setting -- though theirs is in the form of questions and answers.

And, to be honest, Doll Bones reminded me tonally of Emily Brontë, at least. Doll Bones shares with, say, Wuthering Heights a sense of uneasy genre placement -- is it a romance? a gothic horror story? an adventure tale? a coming of age novel? Both books also share a creeping dread of the death of dreams and the pointless expectations that so often accompany adulthood. How much of growing up is a natural process, and how much of it is nothing but a set of counterproductive societal expectations?

I'm not going to make the claim that Doll Bones is a stone cold masterpiece on the level of Wuthering Heights, of course. But it's one of the most interesting children's books I've read in a long while, one that I think will stay with me in a way that not all books, even very good books, do. I think it's highly distinguished in theme and plot, and that the setting of Rust Belt decay is also very well done. In her review, Rachael expressed some reservations about the characters and prose; I think I like both better than she does. The main characters, at least, seemed perfectly three-dimensional, if maybe not as brilliantly-realized as those in The Hidden Summer or P.S. Be Eleven, and if the prose doesn't hit the heights of The Real Boy or The Center of Everything, it does avoid getting in its own way, and features some lines of great beauty.

In a Newbery discussion, I'd probably put Doll Bones in the tier just below The Real Boy and The Center of Everything, in a tightly-bunched pack that also includes Zebra Forest and The Hidden Summer. It will take me a long, long time to forget Doll Bones, however, and it's a title I can see myself coming back to over and over in the years to come.

Though no child reader would be likely to know of it, Gondal is very much like "The Game" that the main characters in Doll Bones play. At least the earliest stages of the Brontës' game involved toy soldiers (which The Game also includes, along with other dolls and figures), and, like the Brontës, Poppy, Zach, and Alice produce writing about their fictional setting -- though theirs is in the form of questions and answers.

And, to be honest, Doll Bones reminded me tonally of Emily Brontë, at least. Doll Bones shares with, say, Wuthering Heights a sense of uneasy genre placement -- is it a romance? a gothic horror story? an adventure tale? a coming of age novel? Both books also share a creeping dread of the death of dreams and the pointless expectations that so often accompany adulthood. How much of growing up is a natural process, and how much of it is nothing but a set of counterproductive societal expectations?

I'm not going to make the claim that Doll Bones is a stone cold masterpiece on the level of Wuthering Heights, of course. But it's one of the most interesting children's books I've read in a long while, one that I think will stay with me in a way that not all books, even very good books, do. I think it's highly distinguished in theme and plot, and that the setting of Rust Belt decay is also very well done. In her review, Rachael expressed some reservations about the characters and prose; I think I like both better than she does. The main characters, at least, seemed perfectly three-dimensional, if maybe not as brilliantly-realized as those in The Hidden Summer or P.S. Be Eleven, and if the prose doesn't hit the heights of The Real Boy or The Center of Everything, it does avoid getting in its own way, and features some lines of great beauty.

In a Newbery discussion, I'd probably put Doll Bones in the tier just below The Real Boy and The Center of Everything, in a tightly-bunched pack that also includes Zebra Forest and The Hidden Summer. It will take me a long, long time to forget Doll Bones, however, and it's a title I can see myself coming back to over and over in the years to come.

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

Mock Newbery List is Coming! Plus a Scary Poster!

Hear ye! Hear ye! On the morrow next, we shall be announcing the final reading list for the Maryland Mock Newbery! Huzzah!

In the meantime, please enjoy this poster that I made for a horror movie adaptation of Rita Williams-Garcia's One Crazy Summer.

In the meantime, please enjoy this poster that I made for a horror movie adaptation of Rita Williams-Garcia's One Crazy Summer.

2014 Second Takes: Courage Has No Color

About this book, Sam said, "This is an extremely well-researched and documented book -- I doubt

anyone will have any of the questions about attribution that came up in

the discussions last year of Bomb." And that's true. The original research and primary sources alone make it an impressive offering. And, as Sam also notes, it's beautifully designed and illustrated.

Of course, Sam also said that, "the prose is effective, but not particularly artful, and the panoramic nature of the book means that even the characters on whom the most time is spent, such as Walter Morris, the man most responsible for the formation of the unit, don't fully emerge as individuals." I think I was more troubled by both of those areas of evaluation than he was. I know that Tanya Lee Stone can write crisp, engaging prose that creates a feeling of suspense, even when she's dealing with an ultimately anticlimactic story, because she did it in Almost Astronauts. That doesn't happen here. The pacing feels off, and the prose is undistinguished.

I also know that it's possible to write a book about an ensemble cast in which each character emerges as a distinct individual, because, again, Stone did it in Almost Astronauts. That kind of careful characterization also set We've Got a Job apart from the many other excellent nonfiction books published last year. In Courage Has No Color though, I gave up trying to tell the members of the Triple Nickles apart.

Overall, I had the sense that Stone didn't have enough material on the Triple Nickles to write a complete book - or that she didn't think the material stood alone as a compelling story - because the book feels bloated with peripheral information. The digression into the Japanese experience during the war isn't long enough to do justice to the subject matter, but it feels too long for this book. Likewise, the last chapter, about post-WWII integration of the armed forces and the legacy of the Triple Nickles, feels long-winded without actually providing that much information.

I'm being pretty harsh in my evaluation of what is, after all, one of the best nonfiction titles of the year, but this seems like a weak year for nonfiction, and I don't think Courage Has No Color will be picking up a Newbery.

Of course, Sam also said that, "the prose is effective, but not particularly artful, and the panoramic nature of the book means that even the characters on whom the most time is spent, such as Walter Morris, the man most responsible for the formation of the unit, don't fully emerge as individuals." I think I was more troubled by both of those areas of evaluation than he was. I know that Tanya Lee Stone can write crisp, engaging prose that creates a feeling of suspense, even when she's dealing with an ultimately anticlimactic story, because she did it in Almost Astronauts. That doesn't happen here. The pacing feels off, and the prose is undistinguished.

I also know that it's possible to write a book about an ensemble cast in which each character emerges as a distinct individual, because, again, Stone did it in Almost Astronauts. That kind of careful characterization also set We've Got a Job apart from the many other excellent nonfiction books published last year. In Courage Has No Color though, I gave up trying to tell the members of the Triple Nickles apart.

Overall, I had the sense that Stone didn't have enough material on the Triple Nickles to write a complete book - or that she didn't think the material stood alone as a compelling story - because the book feels bloated with peripheral information. The digression into the Japanese experience during the war isn't long enough to do justice to the subject matter, but it feels too long for this book. Likewise, the last chapter, about post-WWII integration of the armed forces and the legacy of the Triple Nickles, feels long-winded without actually providing that much information.

I'm being pretty harsh in my evaluation of what is, after all, one of the best nonfiction titles of the year, but this seems like a weak year for nonfiction, and I don't think Courage Has No Color will be picking up a Newbery.

2014 Second Takes: The Center of Everything, by Linda Urban

The Center of Everything is like a brilliantly-constructed box -- or maybe a brilliantly-constructed torus, the shape that recurs throughout the book. Rachael mentioned in her review of the novel how well all the parts fit together, and that stood out to me too as I read the book.

It's a testament to Linda Urban's skill that she manages to produce a book that I unabashedly love out of elements that in general, I don't much care for. This is a book about a small town, filled with quirky characters, about a girl who's lost her grandmother. And yet I was riveted through the whole thing, and genuinely affected by the quiet, but emotionally rich ending.

I've enjoyed Urban's work in the past, but The Center of Everything might well be a new high for her. In the context of this year, it's the only book I've read that I feel can go toe to toe with The Real Boy. It's exceptional in characters, theme, setting, and style, and I think the plot, though low-key, is solid as well.

I'm going to have to think really, really hard about which of those two books would be my final choice (and it may be noted that I still have one book, Doll Bones, left on my Second Takes list). But the simple fact that I feel like The Center of Everything belongs in that conversation with another book that I adore is the highest compliment I know how to pay it.

It's a testament to Linda Urban's skill that she manages to produce a book that I unabashedly love out of elements that in general, I don't much care for. This is a book about a small town, filled with quirky characters, about a girl who's lost her grandmother. And yet I was riveted through the whole thing, and genuinely affected by the quiet, but emotionally rich ending.

I've enjoyed Urban's work in the past, but The Center of Everything might well be a new high for her. In the context of this year, it's the only book I've read that I feel can go toe to toe with The Real Boy. It's exceptional in characters, theme, setting, and style, and I think the plot, though low-key, is solid as well.

I'm going to have to think really, really hard about which of those two books would be my final choice (and it may be noted that I still have one book, Doll Bones, left on my Second Takes list). But the simple fact that I feel like The Center of Everything belongs in that conversation with another book that I adore is the highest compliment I know how to pay it.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

2014 Contenders: Eruption!, by Elizabeth Rusch

Last year was a true banner year for children's nonfiction, featuring such exceptional titles as Moonbird, Temple Grandin, Hope and Tears, Titanic: Voices from the Disaster, We've Got a Job, Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass, and, of course, Bomb. That's an amazing list of books right there, and the fact that they came out in the same twelve-month period is nothing short of astonishing.

I guess it's not a huge surprise that this year's crop of nonfiction has generally paled in comparison. Some of that is just the vagaries of publishing -- Phillip Hoose and Gwyneth Swain, for instance, didn't have a book out this year, and Deborah Hopkinson's new one was historical fiction. Steve Sheinkin and Russell Freedman did have new ones out -- but though both books were certainly good, the general consensus seems to be that they don't quite hit the heights of their titles from last year. In fact, though I've enjoyed several nonfiction books this year (Courage Has No Color and Collector of Skies in particular), I'm not sure there's a single one that I'd put in the same category as the seven titles I listed in the first paragraph.

However, Eruption! has been getting a fair amount of good press, with Jonathan Hunt over at Heavy Medal even touting it as "arguably my favorite nonfiction title of the year." As such, I felt like I had to pick it up, and I was immediately sucked into the story of the brave and resourceful scientists of the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program. The book focuses on two of the VDAP's greatest triumphs -- their studies of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, and Mount Merapi in 2010. In both cases, the VDAP scientists accurately predicted major eruptions a few days before they occurred, enabling evacuations that saved tens of thousands of lives. Elizabeth Rusch's sentence-level writing is engaging, and I thought she did very well at bringing the reader right into the middle of the action.

I have some questions, however, about places where the style -- and, more especially, the editing -- seemed to get in the way of the Presentation of Information item in the Newbery criteria. For instance, the text mentions the technical word "fumaroles" twice, once in a chart on page 10, and in the main text on page 11, without either defining the word or explicitly referring the reader to the glossary in the back. However, when the word appears in the main text on page 15, it's defined within the sentence -- and then defined again, using almost the exact same words, on page 21. Additionally, on page 63, the text lists the name of a village as Dusun Petung, but the photo caption simply calls it Petung. The map on page 8 also misspells the name of Mount Rainier. Those are small points, to be sure, but in an informational text, I don't think we can just ignore them.

When I finished Eruption!, I was glad to have read it, and I felt like I'd learned a lot about an organization I'd never before even heard of. I don't think, however, that it has that je ne sais quoi that the best of last year's titles did, and I find the sloppy editing troubling. I'd recommend in a heartbeat that any public library purchase Eruption! for their collections, but I don't think it's a serious Newbery contender, and I still think Courage Has No Color would be a better Sibert selection.

Published in June by Houghton Mifflin

I guess it's not a huge surprise that this year's crop of nonfiction has generally paled in comparison. Some of that is just the vagaries of publishing -- Phillip Hoose and Gwyneth Swain, for instance, didn't have a book out this year, and Deborah Hopkinson's new one was historical fiction. Steve Sheinkin and Russell Freedman did have new ones out -- but though both books were certainly good, the general consensus seems to be that they don't quite hit the heights of their titles from last year. In fact, though I've enjoyed several nonfiction books this year (Courage Has No Color and Collector of Skies in particular), I'm not sure there's a single one that I'd put in the same category as the seven titles I listed in the first paragraph.

However, Eruption! has been getting a fair amount of good press, with Jonathan Hunt over at Heavy Medal even touting it as "arguably my favorite nonfiction title of the year." As such, I felt like I had to pick it up, and I was immediately sucked into the story of the brave and resourceful scientists of the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program. The book focuses on two of the VDAP's greatest triumphs -- their studies of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, and Mount Merapi in 2010. In both cases, the VDAP scientists accurately predicted major eruptions a few days before they occurred, enabling evacuations that saved tens of thousands of lives. Elizabeth Rusch's sentence-level writing is engaging, and I thought she did very well at bringing the reader right into the middle of the action.

I have some questions, however, about places where the style -- and, more especially, the editing -- seemed to get in the way of the Presentation of Information item in the Newbery criteria. For instance, the text mentions the technical word "fumaroles" twice, once in a chart on page 10, and in the main text on page 11, without either defining the word or explicitly referring the reader to the glossary in the back. However, when the word appears in the main text on page 15, it's defined within the sentence -- and then defined again, using almost the exact same words, on page 21. Additionally, on page 63, the text lists the name of a village as Dusun Petung, but the photo caption simply calls it Petung. The map on page 8 also misspells the name of Mount Rainier. Those are small points, to be sure, but in an informational text, I don't think we can just ignore them.

When I finished Eruption!, I was glad to have read it, and I felt like I'd learned a lot about an organization I'd never before even heard of. I don't think, however, that it has that je ne sais quoi that the best of last year's titles did, and I find the sloppy editing troubling. I'd recommend in a heartbeat that any public library purchase Eruption! for their collections, but I don't think it's a serious Newbery contender, and I still think Courage Has No Color would be a better Sibert selection.

Published in June by Houghton Mifflin

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

2014 Second Takes: Flora & Ulysses: The Illuminated Adventures, by Kate DiCamillo

If there's one thing that I find myself thinking about over and over in the course of writing about books, it's that comedy is terrifically hard to evaluate. And here, with Flora & Ulysses, that again comes into play. Is it funny? I thought it was hysterical, but if you're, say, the kind of person who found last year's Mr. & Mrs. Bunny - Detectives Extraordinaire! overly weird, you're unlikely to agree with me.

As Rachael mentioned in her review, the bits where Ulysses the squirrel writes his poetry are simply beautiful. There's a real emotional center to this book -- as ridiculous as a lot of it is, it isn't just a pile of jokes. That mixture of poignancy and silliness is pure DiCamillo, and though sometimes that feels manipulative to me, I think she pulls it off in Flora & Ulysses.

There was one thing that did bother me, though. I'm starting to grow weary of books that give their characters obsessions with Treasure Island, or Heloise's Hints, or that old standby, the dictionary. There are times where it's effective, but too often, it feels like a writing shortcut to give characters a memorable quirk. Flora is a huge, huge fan of a comic series starring The Amazing Incandesto (as well as its associated "bonus comics"), and I didn't feel like that was particularly effective. It would have been a better book, I think, if DiCamillo had fully trusted the humor and the poetry to carry the novel, rather than shoehorning all the comic book stuff in there too.

Anyway, I think Flora & Ulysses is still quite good, and I think it would be one of the easiest sells to a child reader of anything we've discussed on the blog this year. Even aside from the question of its illustrated nature, however, I don't think it's going to be in the running for the year's major awards.

As Rachael mentioned in her review, the bits where Ulysses the squirrel writes his poetry are simply beautiful. There's a real emotional center to this book -- as ridiculous as a lot of it is, it isn't just a pile of jokes. That mixture of poignancy and silliness is pure DiCamillo, and though sometimes that feels manipulative to me, I think she pulls it off in Flora & Ulysses.

There was one thing that did bother me, though. I'm starting to grow weary of books that give their characters obsessions with Treasure Island, or Heloise's Hints, or that old standby, the dictionary. There are times where it's effective, but too often, it feels like a writing shortcut to give characters a memorable quirk. Flora is a huge, huge fan of a comic series starring The Amazing Incandesto (as well as its associated "bonus comics"), and I didn't feel like that was particularly effective. It would have been a better book, I think, if DiCamillo had fully trusted the humor and the poetry to carry the novel, rather than shoehorning all the comic book stuff in there too.

Anyway, I think Flora & Ulysses is still quite good, and I think it would be one of the easiest sells to a child reader of anything we've discussed on the blog this year. Even aside from the question of its illustrated nature, however, I don't think it's going to be in the running for the year's major awards.

Friday, November 8, 2013

2014 Second Takes: The True Blue Scouts of Sugar Man Swamp

This book. This book, this book, this book. Friends, I have been wrestling with it since last spring, and I still don't know what the heck to do with it.

All of my discerning Goodreads friends love it. Monica Edinger loves it. Lisa Von Drasek loves it. It's on the National Book Award shortlist.

As for me? I picked it up last March or so, got thirty pages in, and promptly threw it over the cubicle wall at Sam. The folksy voice of the intrusive narrator was just nails on a chalkboard to me. Sam agreed.

But time went by, and people weren't liking it any less, so I figured I'd better put it on my list of semi-finalists and give the old girl another chance. This time I alternated between the book and the audiobook, which is read by Lyle Lovett - a great favorite of mine. I thought it might help me appreciate the charms of The True Blue Scouts.

Now, sports fans, I am an easy sell where audiobooks are concerned. The fact is, I just like to sit down and have somebody read me a story, and I hardly care what it is. My daughter is like that too, but more so.

Even so, several chapters into True Blue Scouts - chapters full of raccoonish fretting about the perils of climbing a pine tree - she turned to me and said, "Why doesn't he just climb the tree already?!"

Exactly.

In the end, I was forced to admit that this is probably a very good book, but Ella's question really gets at the heart of what bothers me about it. As Sam put it, "The pacing is leisurely, full of odd digressions and interludes that don't go anywhere, but the tone of the book is insistent, even alarmist, which made me feel rather like the novel was crying wolf at me for most of its duration." I didn't feel like that was as much of a liability here as it was in Keeper, but it did grate on me. Climb the tree already, Bingo. Get to the point.

I have other quibbles too - would a twelve-year-old boy really think that coffee would literally put hair on his chest? - but they're just that. Quibbles. Objectively, True Blue Scouts has a lot of distinguished features. The setting is magnificently realized, the style is both distinguished and individually distinct, and the characters (within the rules of their tall tale framework) are quite vivid. Any problems I have with it come down to a matter of taste. I'm afraid I'm just not cut out for sugar pies.

All of my discerning Goodreads friends love it. Monica Edinger loves it. Lisa Von Drasek loves it. It's on the National Book Award shortlist.

As for me? I picked it up last March or so, got thirty pages in, and promptly threw it over the cubicle wall at Sam. The folksy voice of the intrusive narrator was just nails on a chalkboard to me. Sam agreed.

But time went by, and people weren't liking it any less, so I figured I'd better put it on my list of semi-finalists and give the old girl another chance. This time I alternated between the book and the audiobook, which is read by Lyle Lovett - a great favorite of mine. I thought it might help me appreciate the charms of The True Blue Scouts.

Now, sports fans, I am an easy sell where audiobooks are concerned. The fact is, I just like to sit down and have somebody read me a story, and I hardly care what it is. My daughter is like that too, but more so.

Even so, several chapters into True Blue Scouts - chapters full of raccoonish fretting about the perils of climbing a pine tree - she turned to me and said, "Why doesn't he just climb the tree already?!"

Exactly.

In the end, I was forced to admit that this is probably a very good book, but Ella's question really gets at the heart of what bothers me about it. As Sam put it, "The pacing is leisurely, full of odd digressions and interludes that don't go anywhere, but the tone of the book is insistent, even alarmist, which made me feel rather like the novel was crying wolf at me for most of its duration." I didn't feel like that was as much of a liability here as it was in Keeper, but it did grate on me. Climb the tree already, Bingo. Get to the point.

I have other quibbles too - would a twelve-year-old boy really think that coffee would literally put hair on his chest? - but they're just that. Quibbles. Objectively, True Blue Scouts has a lot of distinguished features. The setting is magnificently realized, the style is both distinguished and individually distinct, and the characters (within the rules of their tall tale framework) are quite vivid. Any problems I have with it come down to a matter of taste. I'm afraid I'm just not cut out for sugar pies.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

2014 Second Takes: P.S. Be Eleven, by Rita Williams-Garcia

Rachael had a lot of good things to say in her original review of P.S. Be Eleven, and a lot of them centered on the characters and setting of the book. After reading the novel myself, I have to agree with her on those two points. The characters are strong, detailed, and well-rounded -- P.S. Be Eleven handles that particular Newbery criterion better than any book I've read this year except maybe The Hidden Summer (which, incidentally, I'm regretting leaving off our semifinal list more and more).

The New York City setting is also vibrant and clear. Plenty of children's books have ❤ed NYC over the years, but P.S. Be Eleven is among the best of them. (I like the fact that it fills in the time period between two of my all-time favorites, the early 1960s of It's Like This, Cat, and the late 1970s of When You Reach Me. Both of those, of course, won the Newbery, so maybe that's a good sign for Rita Williams-Garcia!)

I'm less sold than Rachael, however, about some of the book's other aspects. The ending felt odd to me, as if the book had almost been left unfinished. I thought, reading it, that the novel would come to some kind of sharp, climactic conclusion, but it just sort of peters out. On a similar note, the title comes from the letters that Cecile sends to Delphine, but I didn't feel like the letters were integral to the story as much as they were a device to try and tie the book back to One Crazy Summer.

Speaking of One Crazy Summer, the reader had best have read that book before going on to this one. There are various summaries of and callbacks to the events of Summer in P.S. Be Eleven, but there's simply so much backstory that I think it would be a really tough task to go into P.S. Be Eleven blind.

We have conversations every year about whether a particular book in the Newbery conversation "stands alone." That's not actually in the award criteria, and the committee has given the Newbery to books that clearly don't stand alone (see: The High King, The Grey King, possibly even Dicey's Song), but to the extent that it affects a book's "contribution to American Literature," it's something to possibly keep in mind. That said, I don't think P.S. Be Eleven does indeed "stand alone," though I don't know that it alters the book's literary merit.

At any rate, although I'd put P.S. Be Eleven extremely high on some of the Newbery criteria, I think its weaknesses in plot and construction knock it out of the top five for me. It's good -- very good -- and it what it does well, it does superlatively. I just think that there are books that are better all-around packages this year (The Real Boy, Zebra Forest, The Hidden Summer, From Norvelt to Nowhere, Follow Follow).

However, since it will almost certainly be on our Maryland Mock Newbery shortlist, we'll get a chance to see if our group agrees with me!

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

2014 Contenders: From Norvelt to Nowhere, by Jack Gantos

When last we left Jack Gantos (the character, not the author), the mystery of the murders of the Original Norvelters had been solved, his ever-bleeding nose had been repaired, and he'd even managed to talk some temporary sense into his father. However, once Jack's mother sends him on a trip to accompany the curmudgeonly Miss Volker to Eleanor Roosevelt's grave, everything rapidly deteriorates again. Jack and Miss Volker end up on a journey to Florida -- a journey filled with Classics Illustrated comic books, harpoons, and the vintage Gantos sense of an entire universe spiraling out of the control of a hapless, befuddled narrator.

The last book that Gantos (the author) wrote was, of course, Dead End in Norvelt, which took the 2012 Newbery. I actually think that Nowhere is a stronger book than Dead End -- it's funnier, more emotionally complex, and more thematically deep. There aren't too many sequels to Newbery books that manage to top the original, but I think Nowhere may well be one.

Paradoxically, I also think it's much less likely to win. The 2012 award year was, as we've mentioned before, a really odd one, and Dead End in Norvelt is very much an outlier in the Newbery canon. It's a humorous mystery that won an award that only infrequently goes to mysteries, and almost never goes to something funny. It also represented the longest time between an author's debut and winning the Newbery.

This was partly because the list of 2012 contenders wasn't very deep, and the titles that attracted the most attention were so divisive that it might have been impossible to build consensus around any of them (see: Okay for Now, Breadcrumbs, Junonia). I don't feel like that's the case this year, and I think that's what it would take for another Gantos novel that works in genres and styles that rarely show up in the Newbery to take home the medal.

Additionally, despite the fact that the Newbery criteria state quite clearly that each book is to be considered on its own, without reference to any of an author's other works, there's no precedent for two books in the same series winning the top prize. We've seen, within a series, one book win the Newbery and then another one honor (e.g., Dicey's Song [1983 winner] and A Solitary Blue [1984 honor]); a book take an honor and then another one win (The Dark is Rising [1974 honor] and The Grey King [1976 winner]; The Black Cauldron [1966 honor] and The High King [1969 winner]); and several books in the same series be given honors (all five of Laura Ingalls Wilder's honor titles); but never two winners from the same set. It's possible that someday, we'll see it happen, but I just don't see the Norvelt books as being the ones to break that barrier.

Anyone who enjoyed Dead End will likely also enjoy Nowhere, and I think it's an excellent novel. Just don't put all your money on it winning the Newbery.

Published in September by Farrar Straus Giroux / MacMillan

The last book that Gantos (the author) wrote was, of course, Dead End in Norvelt, which took the 2012 Newbery. I actually think that Nowhere is a stronger book than Dead End -- it's funnier, more emotionally complex, and more thematically deep. There aren't too many sequels to Newbery books that manage to top the original, but I think Nowhere may well be one.

Paradoxically, I also think it's much less likely to win. The 2012 award year was, as we've mentioned before, a really odd one, and Dead End in Norvelt is very much an outlier in the Newbery canon. It's a humorous mystery that won an award that only infrequently goes to mysteries, and almost never goes to something funny. It also represented the longest time between an author's debut and winning the Newbery.

This was partly because the list of 2012 contenders wasn't very deep, and the titles that attracted the most attention were so divisive that it might have been impossible to build consensus around any of them (see: Okay for Now, Breadcrumbs, Junonia). I don't feel like that's the case this year, and I think that's what it would take for another Gantos novel that works in genres and styles that rarely show up in the Newbery to take home the medal.

Additionally, despite the fact that the Newbery criteria state quite clearly that each book is to be considered on its own, without reference to any of an author's other works, there's no precedent for two books in the same series winning the top prize. We've seen, within a series, one book win the Newbery and then another one honor (e.g., Dicey's Song [1983 winner] and A Solitary Blue [1984 honor]); a book take an honor and then another one win (The Dark is Rising [1974 honor] and The Grey King [1976 winner]; The Black Cauldron [1966 honor] and The High King [1969 winner]); and several books in the same series be given honors (all five of Laura Ingalls Wilder's honor titles); but never two winners from the same set. It's possible that someday, we'll see it happen, but I just don't see the Norvelt books as being the ones to break that barrier.

Anyone who enjoyed Dead End will likely also enjoy Nowhere, and I think it's an excellent novel. Just don't put all your money on it winning the Newbery.

Published in September by Farrar Straus Giroux / MacMillan

2014 Contenders: Far Far Away, by Tom McNeal

What do the Newbery criteria have to say about age-appropriateness?

2. A “contribution to American literature for children” shall be a book for which children are an intended potential audience. The book displays respect for children’s understandings, abilities, and appreciations. Children are defined as persons of ages up to and including fourteen, and books for this entire age range are to be considered.

Many books fall obviously inside or outside the "up to and including fourteen" range. The Year of Billy Miller is in. Looking for Alaska is out (forgive the old example - I haven't read any YA this year, unless you count the title currently under discussion). Some books are more difficult to categorize. Age of protagonist can be a indicator, but not always - Hattie Ever After feels like a solid middle grade book, despite the fact that Hattie is seventeen or eighteen. Violence and/or sexual content can also catapult a book out of the Newbery range. If all else fails, you can fall back on a rule of thumb I think I first read on the child_lit listserv: a true children's book always ends on a hopeful note.

So how does Far Far Away measure up? Jeremy and Ginger, the main child characters, are fifteen - a little older than the Newbery range, but children do "read up." There's no sexual content more prurient than a chaste kiss on the lips. And the violence, while present, is more suggestive than graphic. Finally, the ending is categorically happy and hopeful, as befits the fairy tale structure.

BUT.

For its last third, just before the happy ending, the book turns into a true horror novel. There's no bloodshed or brute violence, but things grow uncomfortably dark. Darker than we imagine our Newbery books to be. As dark as real life can get, in fact.

At first that section made me say, "Welp, definitely not a Newbery contender!" And obviously, I won't be handing it to my seven-year-old. But I thought back to what I was reading when I was thirteen and fourteen, and you know what? Those were the years when I discovered Stephen King. I was reading The Shining, Misery, Carrie, etc. And I wasn't the only one. We were also passing around Flowers in the Attic in those days, and whatever V.C. Andrews lacked in literary quality she definitely made up for in pure creepiness. And, heck, in school we were reading Guy de Maupassant and Poe. For all their historical distance, those guys still pack a creepy punch.

Can we really say that Far Far Away is less appropriate for fourteen-year-olds than Maupassant and Poe? When we're supposed to be considering books for the entire age range?

I have a feeling that Far Far Away will make people too uncomfortable to get any Newbery love, but I would argue that it does fall within the Newbery range. And yes, by the way, it is distinguished - in character, in setting, in theme, in style, but probably most of all in plot. I can't think of another book this year that so effectively and methodically tightened the suspense noose. And when the trap was finally sprung, the payoff was dark - yes - but deliciously effective.

Published in June by Knopf Books for Young Readers

Monday, October 28, 2013

2014 Contenders: Africa is My Home, by Monica Edinger

Full disclosure: the About to Mock ranch is very much a Monica Edinger fan club. We love her blog (if by some odd chance, you read us and not her, you should rectify that immediately), we eagerly devour her reviews in The Horn Book and The New York Times, and we're very grateful for her support in our own book discussion endeavors. We think she's awesome, and so I can't help but have that in my mind as I'm reading her work.

Africa is My Home is the fictionalized story of Sarah Margru Kinson, one of a handful of children who happened to be aboard the slave ship Amistad, of Supreme Court and Steven Spielberg fame. It follows her from her childhood in what is now Sierra Leone, through her experiences aboard the ship and in America, and on into her adult life. It's a fascinating read that sheds light on a little-known part of a famous story.

Indeed, though Africa is My Home is a short, heavily illustrated book with a single narrator, the book I was reminded of while reading it was No Crystal Stair. Both books discuss lesser-known figures involved in famous events, and interestingly, in both cases, the author attempted to write the book as straight nonfiction first before realizing that the paucity of firsthand data made that impossible.

I think Africa is the better of the two books, partly because it maintains its focus so well (which was my complaint about No Crystal Stair, though I was really the only one complaining, so take that for what it's worth). But Africa also breaks into poetry occasionally -- poetry that truly sings. Those passages are, in my opinion, the best part of the book, to the point that what I really want now is to read a book of Edinger's poetry. I'd put good money on it being awesome.

The one quibble I had with the book has to do with its being narrated in the first person by Sarah -- but a version of Sarah who is fully grown and looking back on the events of the narrative. This allows for the inclusion of facts and interpretations of events that a child wouldn't necessarily know or comprehend, but I felt like that temporal distance made the book lose some emotional immediacy. It's not a huge issue, but especially given that there's no such emotional gap in the poetic bits, it was something I noticed.

Although it can't be taken into account for Newbery purposes, this is also a truly beautiful-looking book. The illustrations are by Robert Byrd (Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!, Electric Ben), who captures the feel of 19th-century broadsides and maps while still imparting his signature style. It's a great pairing with the text, and the editors of the book should be commended for that.

The Newbery committee historically is very unfriendly to "picture books" -- even comparatively long ones with lots of text -- and if Africa were somehow to win, I think it might be the shortest winner since maybe Sarah, Plain and Tall (1986). That doesn't feel likely to me this year, but if Africa doesn't make the notables list, you'll definitely be able to color me surprised.*