Once an author has written a few books, we often tell ourselves that we know what to expect from them. A Kevin Henkes book will be an existential crisis for elementary schoolers, in the form of a lovingly detailed miniature. A new Jack Gantos title will feature a hapless protagonist in an environment inexorably spiraling out of control, laced with dark humor. Anything by Kate DiCamillo will be funny, but the kind of funny that wears its heart proudly on its sleeve, and it will likely feature at least one animal character.

I thought I had Linda Urban pegged too, as a writer of subdued, carefully-crafted contemporary realism -- someone who would fit well in a group with Cynthia Lord, Gin Phillips, and The Thing About Luck-era Cynthia Kadohata. I never did get around to reading Hound Dog True, but that seemed like a valid assessment of both A Crooked Kind of Perfect and The Center of Everything.

However, Milo Speck, Accidental Agent blows that theory completely away. It's a rollicking, funny, fantasy adventure that's bold and clever, and on the surface at least, has nothing to do with anything Urban has ever written before. In the Author's Note, Urban names Roald Dahl and Edward Eager as her primary influences, and that should give you an accurate idea of how the book reads.

The plot isn't easy to summarize, but involves the adventures of Milo Speck, who falls through a clothes dryer and into the land of Ogregon. Hijinks involving ogres, giant turkeys, secret agents, and more follow. It's the sort of inspired lunacy that often attracts young readers -- it would shock me if this doesn't end up being Urban's book with the most popular appeal.

Surprisingly -- at least to me -- Urban transitions to this mode with apparent effortlessness. Milo Speck is a charming novel that made me smile on numerous occasions. The ending sets up the possibility of a series, so this may not be the last we hear of our accidental protagonist.

I do think, just based on the way the awards committees tend to lean, that Milo Speck is much less likely to receive any accolades than Urban's previous books, even if it may well prove to be a lasting favorite with readers. It does, however, prove that sometimes, reaching beyond your comfort zone leads to unexpected success.

Published in September by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Thursday, September 17, 2015

Wednesday, September 9, 2015

2016 Contenders: A Handful of Stars, by Cynthia Lord

Lily Dumont lives with her grandparents in small-town Maine. The local economy relies heavily on blueberry farming, and blueberries require migrant workers to pick them. When Lily's blind dog Lucky runs away, and is caught by a migrant girl about Lily's age, Salma Santiago, an unlikely friendship forms.

There are a lot of moving parts in Cynthia Lord's most recent novel: Lily's fraying relationship with her friend Hannah; the uneasiness between the migrant workers and the locals; Lily's desire to raise money for cataract surgery for Lucky; Salma's interest in the Blueberry Queen pageant; residual angst from the absence of Lily's mother; art as a means of self-expression. It's to Lord's credit that the book manages to keep all of those metaphorical balls in the air without dropping any of them. A Handful of Stars is a well-written book, and people who enjoy Lord's ability to write difficult relationships honestly will find a lot to like here.

That being said, I don't know that A Handful of Stars stacks up particularly well against Lord's own oeuvre; I think it's a noticeably weaker book than last year's Half a Chance, and the odds of it replacing Rules (2006) as the first line in any bio of Lord aren't high. While the core pair of Lily and Salma are well-drawn, the rest of the characters didn't seem to have the same life to them. Maybe more importantly, I just didn't feel that invested or interested in the portions that dealt with Lily's mother. (Spoilers follow.)

We don't find out until a good halfway through the book that Lily's mother is actually dead. However, this is information that Lily, who narrates the book, already has, and that everyone around her except Salma already has as well. Lily does mention that she's not a huge fan of talking about it, but if the core idea is that mentioning her mother's death is simply too painful for her, it's too muted to be effective. Instead, it feels like an artificial attempt to inject tension; I felt manipulated as a reader.

The prevalence of dead, missing, or incompetent parents in children's literature is basically its own meme at this point. On one level, it's understandable -- it's hard to be off having awesome adventures or discovering yourself if someone is looking over your shoulder the whole time. On another, if you're going to use that trope, you'd better have something clever or interesting to say about it. (See: Roller Skates, The Higher Power of Lucky, Zebra Forest, The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza, etc.) In A Handful of Stars, there are some elements about Lily's mother's history as a pageant winner, and the relationship between her death and Lily's dog Lucky, but I didn't feel like the absence of parents was really necessary to drive the story. Indeed, I think I would have liked the book better if it had just focused in on Lily and Salma, and eliminated the subplots involving Lily's family.

Even given those points, A Handful of Stars is an above-average book; the recurring intertwined images of blueberries and stars alone are worth the price of admission. There are stronger books in contention for this year's Newbery, however, and Lord herself is capable of writing stronger titles.

Published in May by Scholastic

There are a lot of moving parts in Cynthia Lord's most recent novel: Lily's fraying relationship with her friend Hannah; the uneasiness between the migrant workers and the locals; Lily's desire to raise money for cataract surgery for Lucky; Salma's interest in the Blueberry Queen pageant; residual angst from the absence of Lily's mother; art as a means of self-expression. It's to Lord's credit that the book manages to keep all of those metaphorical balls in the air without dropping any of them. A Handful of Stars is a well-written book, and people who enjoy Lord's ability to write difficult relationships honestly will find a lot to like here.

That being said, I don't know that A Handful of Stars stacks up particularly well against Lord's own oeuvre; I think it's a noticeably weaker book than last year's Half a Chance, and the odds of it replacing Rules (2006) as the first line in any bio of Lord aren't high. While the core pair of Lily and Salma are well-drawn, the rest of the characters didn't seem to have the same life to them. Maybe more importantly, I just didn't feel that invested or interested in the portions that dealt with Lily's mother. (Spoilers follow.)

We don't find out until a good halfway through the book that Lily's mother is actually dead. However, this is information that Lily, who narrates the book, already has, and that everyone around her except Salma already has as well. Lily does mention that she's not a huge fan of talking about it, but if the core idea is that mentioning her mother's death is simply too painful for her, it's too muted to be effective. Instead, it feels like an artificial attempt to inject tension; I felt manipulated as a reader.

The prevalence of dead, missing, or incompetent parents in children's literature is basically its own meme at this point. On one level, it's understandable -- it's hard to be off having awesome adventures or discovering yourself if someone is looking over your shoulder the whole time. On another, if you're going to use that trope, you'd better have something clever or interesting to say about it. (See: Roller Skates, The Higher Power of Lucky, Zebra Forest, The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza, etc.) In A Handful of Stars, there are some elements about Lily's mother's history as a pageant winner, and the relationship between her death and Lily's dog Lucky, but I didn't feel like the absence of parents was really necessary to drive the story. Indeed, I think I would have liked the book better if it had just focused in on Lily and Salma, and eliminated the subplots involving Lily's family.

Even given those points, A Handful of Stars is an above-average book; the recurring intertwined images of blueberries and stars alone are worth the price of admission. There are stronger books in contention for this year's Newbery, however, and Lord herself is capable of writing stronger titles.

Published in May by Scholastic

Wednesday, September 2, 2015

2016 Contenders: Watch Out for Flying Kids!, by Cynthia Levinson

I first heard rumblings about Watch Out for Flying Kids! around a year ago. I was immediately interested, since I thought Cynthia Levinson's last book, We've Got a Job, was excellent, and youth social circuses seemed like a fascinating topic for a nonfiction book. It sounded like a winning combination.

Having now finally been able to obtain and read a copy of Watch Out for Flying Kids!, it pains me to say that this title doesn't hang together as well as We've Got a Job. I think there are two main problems that prevent this one from reaching the heights of its predecessor, and I think it's useful to talk about both of them.

One of the things I really liked about We've Got a Job was the way it managed to intercut the stories of four individual children with the larger events of the Birmingham Children's March, and to do so without losing the thread of the narrative. Watch Out for Flying Kids! isn't much longer than We've Got a Job, but there are now eleven main characters (five kids from the St. Louis Arches, four from the Galilee Circus, and the adult director of each circus), as well as a host of secondary characters. I found it difficult even to keep track of the book's cast, and I felt like I didn't get to spend enough time with any of them for their stories to have weight and heft.

This is especially noticeable because, while We've Got a Job had a clear climax (the March itself), Watch Out for Flying Kids! doesn't really build to a specific moment in the same way. The personal stories of the performers could make up for that muted external narrative, but there are just too many of them, too thinly spread, for it to be effective. Similarly, although there's an overarching theme of learning to build bridges between mistrustful communities, that theme doesn't get a specific dénouement.

The second -- and in my mind, more serious -- problem has to do with the book's support apparatus. It spends four pages of the introduction on an Arabic and Hebrew pronunciation guide, but it contains no glossary of any kind. Because so much of the book is concerned with what's going on in the ring of the circus, and I don't really know the technical terms associated with circus work, that lack made the book nearly unreadable to me. Additionally, especially in the sections of the book set in Israel, there are many discussions of different towns and places, but the book doesn't contain a map. I also would have loved a quick "cast list" reference, but even though there's a sort of "where are they now" section in the afterword, it only included the "main characters."I found the book difficult going without those helps, and I think a child reader might have serious problems navigating the book without these customary aids.

It's clear that the stories of Watch Out for Flying Kids! mean a great deal to Levinson. I'm unconvinced, however, that she translates that importance so that readers can understand it. I'd love to see what Levinson does next, but I don't anticipate Watch Out for Flying Kids! showing up in the YMAs.

Published in August by Peachtree

Having now finally been able to obtain and read a copy of Watch Out for Flying Kids!, it pains me to say that this title doesn't hang together as well as We've Got a Job. I think there are two main problems that prevent this one from reaching the heights of its predecessor, and I think it's useful to talk about both of them.

One of the things I really liked about We've Got a Job was the way it managed to intercut the stories of four individual children with the larger events of the Birmingham Children's March, and to do so without losing the thread of the narrative. Watch Out for Flying Kids! isn't much longer than We've Got a Job, but there are now eleven main characters (five kids from the St. Louis Arches, four from the Galilee Circus, and the adult director of each circus), as well as a host of secondary characters. I found it difficult even to keep track of the book's cast, and I felt like I didn't get to spend enough time with any of them for their stories to have weight and heft.

This is especially noticeable because, while We've Got a Job had a clear climax (the March itself), Watch Out for Flying Kids! doesn't really build to a specific moment in the same way. The personal stories of the performers could make up for that muted external narrative, but there are just too many of them, too thinly spread, for it to be effective. Similarly, although there's an overarching theme of learning to build bridges between mistrustful communities, that theme doesn't get a specific dénouement.

The second -- and in my mind, more serious -- problem has to do with the book's support apparatus. It spends four pages of the introduction on an Arabic and Hebrew pronunciation guide, but it contains no glossary of any kind. Because so much of the book is concerned with what's going on in the ring of the circus, and I don't really know the technical terms associated with circus work, that lack made the book nearly unreadable to me. Additionally, especially in the sections of the book set in Israel, there are many discussions of different towns and places, but the book doesn't contain a map. I also would have loved a quick "cast list" reference, but even though there's a sort of "where are they now" section in the afterword, it only included the "main characters."I found the book difficult going without those helps, and I think a child reader might have serious problems navigating the book without these customary aids.

It's clear that the stories of Watch Out for Flying Kids! mean a great deal to Levinson. I'm unconvinced, however, that she translates that importance so that readers can understand it. I'd love to see what Levinson does next, but I don't anticipate Watch Out for Flying Kids! showing up in the YMAs.

Published in August by Peachtree

Tuesday, September 1, 2015

2016 Second Takes: Circus Mirandus, by Cassie Beasley

Circus Mirandus.

The publisher hyped it.

Sam loved it.

Brandy hated it.

As for me? Well, don't mess with me, folks, because I'm Mr. In Between.

I think first-time-novelist Cassie Beasley does a lot of things well in this book. Most notably, she pulls off that mothball-scented Olde Time Storyteller voice that can be magical and engaging, but is so often cloying and off-putting instead. I have spent a lot of time thinking about what it is, exactly, that makes a particular instance of this style effective or ineffective, and I've come up empty-handed. It may just boil down to personal taste. For me, it doesn't work in The Night Gardener or A Snicker of Magic. It does work in The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, and it does work in Circus Mirandus. Your mileage may vary.

Also notable - possibly even more notable - is the way Beasley portrays an irredeemable character. Characters who are puuuuure eeeeeeville don't bother me, necessarily - I can appreciate a Cruella deVil - but I know that Sam hates them. So I had to ask him, after I finished Circus Mirandus: what makes Victoria different? His best answer was that she rings true as a sociopath, and I have to agree. She's less a mustache-twirling villain and more of a John Wayne Gacy. Which makes her scary as hell.

Finally: circuses. It's hard to sell me on them. The Night Circus is the first book that made me actually want to visit the circus in question, and that made me even more skeptical about Circus Mirandus. Surely The Night Circus had fully covered the Circus Acts That Rachael Might Enjoy ground, and this would only be a retread. But it's not! This circus sounds great, and if not completely original, at least charmingly re-imagined.

Maybe I only like magical circuses.

Anyway, if that all makes it sound like I liked this book a lot, well, I did. I do think it's a bit rough around the edges, though. Brandy complains about character development, and I do think that's a weak point, especially with the secondary characters. As much as I wanted to like her, Jenny never felt like a real person to me, and even Ephraim (especially older Ephraim) is more idea than person.

There are also some questionable plot choices. I don't want to spoil anything, but I didn't think the final test of the book didn't made sense in terms of the book's internal logic. Sorry to vagueblog.

In a year with The War That Saved My Life in it, as well as new Laura Amy Schlitz and Rebecca Stead novels coming out soon, I just don't think Circus Mirandus is The Most Distinguished. It is, however, a deeply satisfying novel.

The publisher hyped it.

Sam loved it.

Brandy hated it.

As for me? Well, don't mess with me, folks, because I'm Mr. In Between.

I think first-time-novelist Cassie Beasley does a lot of things well in this book. Most notably, she pulls off that mothball-scented Olde Time Storyteller voice that can be magical and engaging, but is so often cloying and off-putting instead. I have spent a lot of time thinking about what it is, exactly, that makes a particular instance of this style effective or ineffective, and I've come up empty-handed. It may just boil down to personal taste. For me, it doesn't work in The Night Gardener or A Snicker of Magic. It does work in The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, and it does work in Circus Mirandus. Your mileage may vary.

Also notable - possibly even more notable - is the way Beasley portrays an irredeemable character. Characters who are puuuuure eeeeeeville don't bother me, necessarily - I can appreciate a Cruella deVil - but I know that Sam hates them. So I had to ask him, after I finished Circus Mirandus: what makes Victoria different? His best answer was that she rings true as a sociopath, and I have to agree. She's less a mustache-twirling villain and more of a John Wayne Gacy. Which makes her scary as hell.

Finally: circuses. It's hard to sell me on them. The Night Circus is the first book that made me actually want to visit the circus in question, and that made me even more skeptical about Circus Mirandus. Surely The Night Circus had fully covered the Circus Acts That Rachael Might Enjoy ground, and this would only be a retread. But it's not! This circus sounds great, and if not completely original, at least charmingly re-imagined.

Maybe I only like magical circuses.

Anyway, if that all makes it sound like I liked this book a lot, well, I did. I do think it's a bit rough around the edges, though. Brandy complains about character development, and I do think that's a weak point, especially with the secondary characters. As much as I wanted to like her, Jenny never felt like a real person to me, and even Ephraim (especially older Ephraim) is more idea than person.

There are also some questionable plot choices. I don't want to spoil anything, but I didn't think the final test of the book didn't made sense in terms of the book's internal logic. Sorry to vagueblog.

In a year with The War That Saved My Life in it, as well as new Laura Amy Schlitz and Rebecca Stead novels coming out soon, I just don't think Circus Mirandus is The Most Distinguished. It is, however, a deeply satisfying novel.

Thursday, August 27, 2015

2016 Contenders: The Jumbies, by Tracey Baptiste

Corinne La Mer has never believed in jumbies, the supernatural creatures that some think haunt the forests of her island. However, after she chases an agouti into the forest on All Hallows' Eve, the evidence mounts that the jumbies may be much more real than Corinne had ever believed -- and that she and her ragtag group of friends may be the only ones who can stop them.

There's a lot in The Jumbies to admire. At its heart, it's a pure folktale story, one based in a deep understanding of several strains of Caribbean lore. (Author Tracey Baptiste is originally from Trinidad, and has stated that the concept for the book was inspired by a traditional Haitian story.) Corinne is a likable protagonist, and her fellow islanders are also interesting and sympathetic -- especially the orphaned brothers, Bouki and Malik. The island setting, with the ominous shadow of the forest always hanging over everything, also comes alive within the pages.

The Jumbies isn't without flaws, however, and I think the primary one is what I usually call "the Paradise Lost problem": an antagonist who is so strongly written, and whose motives can be construed sympathetically enough, that the ostensible point of the book is undercut. The villain of The Jumbies is Severine, the ruler of the other jumbies. She despises the humans, and is willing to fight in any number of ways to control or defeat them, and Corinne is her main target.

Baptiste makes no secret of the fact that we're meant to dislike Severine; her own author's note states, "Severine is everything I expect a jumbie to be -- tricky, mean, and selfish -- with the added bonus of thinking she's better than everyone else." It's true that Severine displays these characteristics, and is a formidable opponent. On the other hand, she's someone who has lost a great deal; her sister is dead, and her island has been invaded by humans, who have no respect for the forest, and who don't even acknowledge the existence of her and her kind. Severine's methods leave something to be desired, but it's easy enough to see her as an anticolonialist leader of the mistreated indigenous inhabitants to make her demonization problematic. (Baptiste tries to deal with some of this in the ending, with a discussion of discovering "a way to live together," but by that point, the accumulated weight of the narrative is too great to be brushed quickly aside). Severine also clearly wants to have a family again, and if those desires have been twisted and warped in her head, they're still hard for me to completely discredit.

I hope many children find and enjoy The Jumbies. It's a lovely blend of the familiar and the new, and I think plenty of readers will like it. I think it's too internally conflicted to entirely succeed, however, and I think that will keep the book from rising to the top of the Newbery heap.

Published in April by Algonquin / Workman

There's a lot in The Jumbies to admire. At its heart, it's a pure folktale story, one based in a deep understanding of several strains of Caribbean lore. (Author Tracey Baptiste is originally from Trinidad, and has stated that the concept for the book was inspired by a traditional Haitian story.) Corinne is a likable protagonist, and her fellow islanders are also interesting and sympathetic -- especially the orphaned brothers, Bouki and Malik. The island setting, with the ominous shadow of the forest always hanging over everything, also comes alive within the pages.

The Jumbies isn't without flaws, however, and I think the primary one is what I usually call "the Paradise Lost problem": an antagonist who is so strongly written, and whose motives can be construed sympathetically enough, that the ostensible point of the book is undercut. The villain of The Jumbies is Severine, the ruler of the other jumbies. She despises the humans, and is willing to fight in any number of ways to control or defeat them, and Corinne is her main target.

Baptiste makes no secret of the fact that we're meant to dislike Severine; her own author's note states, "Severine is everything I expect a jumbie to be -- tricky, mean, and selfish -- with the added bonus of thinking she's better than everyone else." It's true that Severine displays these characteristics, and is a formidable opponent. On the other hand, she's someone who has lost a great deal; her sister is dead, and her island has been invaded by humans, who have no respect for the forest, and who don't even acknowledge the existence of her and her kind. Severine's methods leave something to be desired, but it's easy enough to see her as an anticolonialist leader of the mistreated indigenous inhabitants to make her demonization problematic. (Baptiste tries to deal with some of this in the ending, with a discussion of discovering "a way to live together," but by that point, the accumulated weight of the narrative is too great to be brushed quickly aside). Severine also clearly wants to have a family again, and if those desires have been twisted and warped in her head, they're still hard for me to completely discredit.

I hope many children find and enjoy The Jumbies. It's a lovely blend of the familiar and the new, and I think plenty of readers will like it. I think it's too internally conflicted to entirely succeed, however, and I think that will keep the book from rising to the top of the Newbery heap.

Published in April by Algonquin / Workman

Tuesday, August 25, 2015

2016 Contenders: What Pet Should I Get?, by Dr. Seuss

I find posthumously published works fascinating, and one of the interesting things about them is the varied states in which the original manuscripts had been left. At one end are books such as The Dark Frigate (the 1924 Newbery winner), where Charles Hawes had actually already delivered the final manuscript to his publisher before dying. At the other end would be something like Franz Kafka's Amerika, which has such an enormous unwritten hole in the middle that it's not even clear how the author intended to get the narrative to its conclusion.

What Pet Should I Get?, which finally reached publication almost two and a half decades after the death of its author, occupies a place somewhere in between those extremes. The manuscript, which was rediscovered a couple of years ago, contained 16 uncolored illustrations. The text was essentially complete, but Seuss's working method was to type the words, cut them up, and then affix them to the illustrations with tape, taping over the old words with new ones if he chose to make alterations. However, the tape had come loose, making it difficult to ascertain exactly which version of the text had been intended. (The New York Times article I linked to there is a fascinating read if you want more detail on how the book came to be.)

The reconstruction was supervised by Cathy Goldsmith, the last person left at Random House who had actually worked with Seuss, having done the design and art direction for his last handful of titles. This reconstituted version arrived on bookstore (and library!) shelves in July, providing a surprise coda to Seuss's career.

Maybe the first thing to take note of is that this isn't a late-period work that Seuss died before finishing up. Rather, it dates from sometime during his middle period, the era of The Cat in the Hat Comes Back (1958), Happy Birthday to You! (1959), and Green Eggs and Ham (1960). The design of the (unnamed) protagonists is almost identical to those of One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (1960), and one possible theory is that What Pet Should I Get? is some sort of embryonic version of or starting point for One Fish. (There are no surviving notes about what Seuss was trying to accomplish in this book -- or why he shelved it -- and so everything at this point is conjecture.)

I was excited to see What Pet Should I Get? come out, because I love Seuss's work so much, and it looms large in my formative reading experiences. However, I think that, once the publicity around the book dies down, we'll see it as an interesting footnote to his career, but no more. Seuss's loping, tongue-twisting meter is relatively easy to parody, but the final texts of his books were the result of near-inhuman levels of revision -- one reason that, although his style is often imitated, it's essentially never equaled. The rhymes and rhythms of What Pet Should I Get? felt noticeably rougher than those of the classic titles he produced during the late '50s and early '60s, and I'm not convinced he would have let the text stand as it is if he had chosen to prepare it for publication.

The ending of the book [spoiler alert!] is also somewhat odd. After running through a long list of possible pets, the siblings who serve as our protagonists make their selection -- but they don't tell us what pet they've chosen, and the final illustration simply shows the eyes of an unidentifiable shape peeking out of the basket that the children are taking home. Seuss wasn't above ending his books on a rhetorical question ("What would you do, if your mother asked you?" from The Cat in the Hat), or even a cliffhanger (the scene of the generals perched on the wall, deciding whether or not to drop their bombs on the last page of The Butter Battle Book, is about as tense of an ending as you'll see), but this ending just felt out of place to me. What Pet Should I Get? is a book written at a level more like that in Seuss's easy readers than that of his longer, more challenging works, and although you could make an argument that the ending is set up that way to allow kids to use their imaginations to finish the story, it still felt to me like running into a wall on the last page.

Although Dr. Seuss is one of the most important figures in the history of American children's literature, he didn't actually do as well in the ALSC awards as I might have thought -- three Caldecott Honors (for McElligot's Pool in 1948, Bartholomew and the Oobleck in 1950, and If I Ran the Zoo in 1951), but zero Caldecott wins, and zero mentions on the Newbery rolls. I'd love to see him win the Geisel award for this one, just for the neatness of having someone win an established award that's already named after them, but I don't think it's actually a good enough book for that to happen. The Newbery is out of the question, and given that the art had to be colorized by later editors, I doubt the Caldecott committee will go for it either. What Pet Should I Get? is a fascinating historical curiosity, but no more than that.

Published in July by Random House

What Pet Should I Get?, which finally reached publication almost two and a half decades after the death of its author, occupies a place somewhere in between those extremes. The manuscript, which was rediscovered a couple of years ago, contained 16 uncolored illustrations. The text was essentially complete, but Seuss's working method was to type the words, cut them up, and then affix them to the illustrations with tape, taping over the old words with new ones if he chose to make alterations. However, the tape had come loose, making it difficult to ascertain exactly which version of the text had been intended. (The New York Times article I linked to there is a fascinating read if you want more detail on how the book came to be.)

The reconstruction was supervised by Cathy Goldsmith, the last person left at Random House who had actually worked with Seuss, having done the design and art direction for his last handful of titles. This reconstituted version arrived on bookstore (and library!) shelves in July, providing a surprise coda to Seuss's career.

Maybe the first thing to take note of is that this isn't a late-period work that Seuss died before finishing up. Rather, it dates from sometime during his middle period, the era of The Cat in the Hat Comes Back (1958), Happy Birthday to You! (1959), and Green Eggs and Ham (1960). The design of the (unnamed) protagonists is almost identical to those of One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish (1960), and one possible theory is that What Pet Should I Get? is some sort of embryonic version of or starting point for One Fish. (There are no surviving notes about what Seuss was trying to accomplish in this book -- or why he shelved it -- and so everything at this point is conjecture.)

I was excited to see What Pet Should I Get? come out, because I love Seuss's work so much, and it looms large in my formative reading experiences. However, I think that, once the publicity around the book dies down, we'll see it as an interesting footnote to his career, but no more. Seuss's loping, tongue-twisting meter is relatively easy to parody, but the final texts of his books were the result of near-inhuman levels of revision -- one reason that, although his style is often imitated, it's essentially never equaled. The rhymes and rhythms of What Pet Should I Get? felt noticeably rougher than those of the classic titles he produced during the late '50s and early '60s, and I'm not convinced he would have let the text stand as it is if he had chosen to prepare it for publication.

The ending of the book [spoiler alert!] is also somewhat odd. After running through a long list of possible pets, the siblings who serve as our protagonists make their selection -- but they don't tell us what pet they've chosen, and the final illustration simply shows the eyes of an unidentifiable shape peeking out of the basket that the children are taking home. Seuss wasn't above ending his books on a rhetorical question ("What would you do, if your mother asked you?" from The Cat in the Hat), or even a cliffhanger (the scene of the generals perched on the wall, deciding whether or not to drop their bombs on the last page of The Butter Battle Book, is about as tense of an ending as you'll see), but this ending just felt out of place to me. What Pet Should I Get? is a book written at a level more like that in Seuss's easy readers than that of his longer, more challenging works, and although you could make an argument that the ending is set up that way to allow kids to use their imaginations to finish the story, it still felt to me like running into a wall on the last page.

Although Dr. Seuss is one of the most important figures in the history of American children's literature, he didn't actually do as well in the ALSC awards as I might have thought -- three Caldecott Honors (for McElligot's Pool in 1948, Bartholomew and the Oobleck in 1950, and If I Ran the Zoo in 1951), but zero Caldecott wins, and zero mentions on the Newbery rolls. I'd love to see him win the Geisel award for this one, just for the neatness of having someone win an established award that's already named after them, but I don't think it's actually a good enough book for that to happen. The Newbery is out of the question, and given that the art had to be colorized by later editors, I doubt the Caldecott committee will go for it either. What Pet Should I Get? is a fascinating historical curiosity, but no more than that.

Published in July by Random House

Wednesday, August 19, 2015

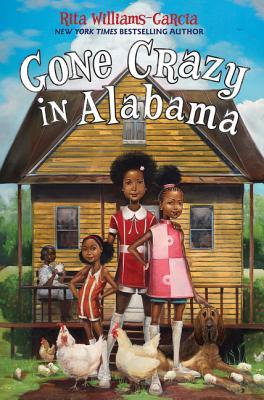

2016 Contenders: Gone Crazy in Alabama, by Rita Williams-Garcia

This was one of my most anticipated books of the year, partly because I was lucky enough to talk with the author about it a whole year before it came out. I was looking forward to the conclusion of the Gaither sisters' story arc, as well as the southern setting and family history.

This was one of my most anticipated books of the year, partly because I was lucky enough to talk with the author about it a whole year before it came out. I was looking forward to the conclusion of the Gaither sisters' story arc, as well as the southern setting and family history.When we rejoin Delphine, Vonetta, and Fern, they are on their way to the Greyhound terminal to begin their journey to visit Big Ma and her mother, Ma Charle,s in rural Alabama. There are several potential sources of conflict, both overt and less obvious. Pa's new wife ("Mrs.") is pregnant. The friction between Delphine and Vonetta is still present, as is Vonetta's resentment towards Uncle Darnell, who's out of rehab and living with Big Ma. (It's a difficult time all around for Vonetta). And then there's the bad blood - buckets of it - between Ma Charles and her half-sister, Miss Trotter. The two sisters live on opposite sides of the same creek, but haven't spoken in decades. Oh, and the family ties to the Klan.

If you think that all makes Gone Crazy in Alabama sound like an awfully ambitious novel, then you are correct. Williams-Garcia has a lot of plot threads to weave together, a new setting and several new characters to introduce, and a trilogy to bring to a satisfying close. For the most part, she accomplishes all of it with finesse. The relationship among the three sisters, especially Delphine and Vonetta, is going through some growing pains, and the resolution of that arc is poignant, as is Vonetta's reconciliation with Uncle Darnell. The Alabama setting - lazy and idyllic on the surface, complicated underneath - is well-realized. There are several intriguing new characters, especially Ma Charles and Miss Trotter, whose mutual sniping provides much of the book's humor.

On the whole though, this is not nearly as funny a book as either of the previous two. There is a brush with tragedy that takes up several chapters, but even before that, most of the characters are going through difficult times for various reasons. That's all handled deftly enough that it doesn't weigh down the narrative, but some of the family history does slow the pace. Telling it through Ma Charles and Miss Trotter's dueling narratives is clever, but it's still a lot of history to get through, and as a reader I often felt lost. Your mileage may vary.

Taken as a whole, Gone Crazy showcases the lovely prose, sharp dialogue, and larger-than-life situations that Rita Williams-Garcia writes so well. The many fans of the Gaither sisters will find it a satisfying conclusion to the series.

Published in April by Amistad/HarperCollins

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)