This past weekend, I was having brunch with two of my favorite people, Sam and Rachael, and the inevitable topic of conversation among a gathering of book lovers came up: “Whatcha reading?” I told them I was reading Crenshaw by Katherine Applegate. They asked if I was liking it. I sighed. I said I didn’t know how I felt about it. I told them the basic plot, and Sam said “Oh, it’s like Harvey for kids.” And I realized he was exactly correct, and that indeed I didn’t know how I felt about a Harvey for kids.

Harvey, for those who aren’t familiar, is a play by Mary Chase, which was famously adapted to a 1950 film starring Jimmy Stewart. It’s the story of a man named Elwood P. Dowd, who has a friend named Harvey, who he says is a six foot tall walking rabbit. Elwood’s family wonders if they should have him committed. There are clues that lead you to question whether Harvey is imaginary or just invisible to everyone but Elwood, but the general consensus is that he’s suffering from a delusion, but it’s a delusion that isn’t hurting anyone, least of all kind and caring Elwood, so he is spared the sanitarium.

Crenshaw is very much a nod to Harvey. Applegate even opens the book with a quote from the play. It’s the story of a boy named Jackson. Jackson is a fifth grader who loves facts. He’s very logical, values honesty, and wants to be scientist. When he was in first grade he had an imaginary friend, a very large talking cat named Crenshaw, but that’s baby stuff, and he’s outgrown Crenshaw. Or so he thinks. Much to his chagrin, Crenshaw has shown up in his life again.

Come to find out, Jackson met Crenshaw when his family was homeless. Both his parents lost their jobs. In addition to struggling financially, Jackson’s dad was also diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. When they could no longer afford to live in their house, the entire family - Jackson, his parents, his sister Robin who was just a baby then, and their dog Aretha - moved into their minivan. Times were very hard, and having a friend helped, so Crenshaw became a part of Jackson’s life. Eventually Jackson’s parents saved enough money for an apartment and re-establish some stability.

That was years ago, but lately Jackson’s noticed some serious signs of insecurity - a distinct lack of variety of food in the pantry, frequent yard sales, his parents arguing about applying for assistance - and he’s frankly scared to be homeless again. He’s also frustrated by his parents who insist on changing the subject when it arises or feigning that things are better than they are. It’s about this time Crenshaw reappears.

There were things about Crenshaw that were problematic for me.

For one, the character of Crenshaw is kind of pompous. I mean, he’s a cat, so I suppose that’s to be expected. But there are moments I felt he was impatient with Jackson, who is befuddled by his return. He alludes to being smarter than Jackson, which I guess could be true, but isn’t very friendly, and what is an imaginary friend supposed to be if not friendly?

There are a few Harvey-esque moments where you may question whether Crenshaw is truly an invention of Jackson’s stressed imagination, or if he’s… well… something else? So I guess you could categorize the book as magical realism, and if you go into it prepared for that kind of story you may enjoy it more than I did.

Another, totally valid in my opinion, way to read Crenshaw is as a horror story.

I recently had an in-depth online conversation with several friends about whether or not Halloween, and “scary” things in general, have been too toned down, to make things “kid-friendly.” What prompted the conversation was during a twilight walk through my neighborhood I realized that Halloween here had basically turned into “orange Christmas,” with twinkling lights replacing any more menacing decorations. Even the jack-o-lanterns looked cute. Traumatizing children is a real concern, of course, and caregivers should know and respect their children enough to not expose them to things they can’t handle yet. Trick-or-treating is supposed to fun. But it’s also supposed to be scary! Is it right to throw away traditions so we won’t upset anyone? Is it wrong to spook our kids every now and then, especially when we know danger isn’t actually present? I cited Grimm fairy tales, and an Austrian Krampuslauf, as examples of safe but scary things for children. Maybe I was a weird kid, but I liked creepy stuff, like Tim Burton movies, and Alvin Schwartz books, when I was young. And I tend to believe experiencing fear through media can help children be resilient when forced to face fear in real life. Are there monsters in my closet? Definitely not. The conversation unexpectedly meandered into a discussion about what is actually scary in the world - things like war, hunger, and social injustice - and how long we ought to protect children from these things, to maintain their innocence. I had not considered a correlation between the horror of ghosts and witches and things that are realistically scary. Like becoming homeless. And I think this idea very much colored my reading of Crenshaw.

Jackson is scared of his family being homeless again. He’s scared there won’t be enough to eat. He’s also scared when his dad has to use a cane, and I think it’s safe to say he’s a bit scared of the enormous talking cat he didn’t invite back into his life, showing up all over the place, making him question his own sanity. I could see this book truly distressing a sensitive reader. I work in a public library where homelessness and hunger are not far-fetched concerns for many in our service area, and I know kids who are housing insecure and food insecure. By the way, I want to give big ups to the librarian in this book, who is helpful and non-judgmental. Way to be, fictional librarian. You are a hero.

I found the ending of Crenshaw to be a bit ambiguous. Throughout the book the reader is lead to believe Crenshaw is only present when Jackson is in need (even if he doesn’t think he is in need). When Jackson’s family’s financial troubles appear to be resolved, at least for the time being, we presume Crenshaw will go away again, but he doesn’t. I was unsatisfied by this, because I wanted Jackson to be “okay” and I’m not sure him continuing to see and hear things others cannot constitutes being okay. But if Harvey is the precedent, I suppose it’s fine to just leave the story there?

I think Crenshaw is probably under consideration for the Newbery, however I don’t know how strong a contender it is. I don’t think it's as finely crafted as Applegate’s 2013 winner The One and Only Ivan. But it is a thought-provoking, opinion-inspiring novel, so the committee will at least have a possibly rollicking, possibly raucous, discussion about it ahead of them. Let the literary throw-down commence! Oh, and...

Friday, October 23, 2015

Friday, October 9, 2015

2016 Contenders: Fuzzy Mud, by Louis Sachar

Marshall Walsh's life has steadily been getting worse for quite some time, and today, bully Chad Hilligas has promised to fight him after school. Not wanting to engage, Marshall -- along with his neighbor Tamaya Dhilwaddi, who walks to and from school with him -- takes a shortcut through the woods, even though they're not supposed to do so.

What happens next threatens the lives of all three children, as well as those of everyone else in the town of Heath Cliff, Pennsylvania -- and possibly further afield. Something has happened at SunRay Farm, a place where eccentric scientist Jonathan Fitzman has been researching alternative biofuel, and that something has terrifying repercussions.

The most obvious point of comparison for Fuzzy Mud is probably Carl Hiassen's children's novels, given their shared concern for environmental themes. The book that Fuzzy Mud most reminded me of, however, wasn't a children's book at all, but rather, The Andromeda Strain, Michael Crichton's 1969 techno-thriller about a deadly, mutating pathogen. Both books ask hard questions about the ways in which technological progress can accidentally have deadly results, and both are threaded with nail-biting tension. Indeed, I thought the menacing tone of Fuzzy Mud -- especially in the scenes that take place in the woods -- was its finest feature.

To address what I felt was the book's biggest weakness, it's useful to go back to the Crichton comparison. (Spoilers follow.) The plot of The Andromeda Strain starts with the scenes of horror in the small town where all but two of the inhabitants have been killed by the title infection. Once it's discovered that a pathogen is involved, the story shifts to the scientists who are trying to understand the infection and develop a cure. Fuzzy Mud pulls off the equivalent of the first part with aplomb -- the scenes in which Tamaya slowly realizes what is happening to her are stunning, and the moment where she finds a nearly-dead Chad in the woods is utterly brilliant. However, the equivalent of the second part felt perfunctory and rushed, and I think the reason is that, because Sachar doesn't want to cut away from his child protagonists for very long, and all three of them are in the hospital and incapacitated, he's essentially painted himself into a corner.

In order for the second part to feel like it's of equal weight to the first, Sachar probably would have had to add in some other child characters who might have been able to be directly involved in the search for a cure -- or, possibly, to be willing to spend more time with secondary characters like Monica or Marshall's family as they deal with the quarantine under which the town is placed. As it stands, the novel feels almost more like one of those 1950s-era short films for students, the kind that told half of a story with thorny moral and ethical problems, and then stopped to ask "What would YOU do?" This is the rare 190-page children's book that really cries out to be longer.

All that said, Fuzzy Mud is still a very good book. As far as Sachar's work goes, however, it's not on the level of Holes or Sideways Stories from Wayside School, and as far as this year's crop of books goes, I don't think it reaches the heights of Circus Mirandus or Moonpenny Island (among others), and I don't expect it to take home the Newbery Medal.

Published in August by Delacorte / Random House

What happens next threatens the lives of all three children, as well as those of everyone else in the town of Heath Cliff, Pennsylvania -- and possibly further afield. Something has happened at SunRay Farm, a place where eccentric scientist Jonathan Fitzman has been researching alternative biofuel, and that something has terrifying repercussions.

The most obvious point of comparison for Fuzzy Mud is probably Carl Hiassen's children's novels, given their shared concern for environmental themes. The book that Fuzzy Mud most reminded me of, however, wasn't a children's book at all, but rather, The Andromeda Strain, Michael Crichton's 1969 techno-thriller about a deadly, mutating pathogen. Both books ask hard questions about the ways in which technological progress can accidentally have deadly results, and both are threaded with nail-biting tension. Indeed, I thought the menacing tone of Fuzzy Mud -- especially in the scenes that take place in the woods -- was its finest feature.

To address what I felt was the book's biggest weakness, it's useful to go back to the Crichton comparison. (Spoilers follow.) The plot of The Andromeda Strain starts with the scenes of horror in the small town where all but two of the inhabitants have been killed by the title infection. Once it's discovered that a pathogen is involved, the story shifts to the scientists who are trying to understand the infection and develop a cure. Fuzzy Mud pulls off the equivalent of the first part with aplomb -- the scenes in which Tamaya slowly realizes what is happening to her are stunning, and the moment where she finds a nearly-dead Chad in the woods is utterly brilliant. However, the equivalent of the second part felt perfunctory and rushed, and I think the reason is that, because Sachar doesn't want to cut away from his child protagonists for very long, and all three of them are in the hospital and incapacitated, he's essentially painted himself into a corner.

In order for the second part to feel like it's of equal weight to the first, Sachar probably would have had to add in some other child characters who might have been able to be directly involved in the search for a cure -- or, possibly, to be willing to spend more time with secondary characters like Monica or Marshall's family as they deal with the quarantine under which the town is placed. As it stands, the novel feels almost more like one of those 1950s-era short films for students, the kind that told half of a story with thorny moral and ethical problems, and then stopped to ask "What would YOU do?" This is the rare 190-page children's book that really cries out to be longer.

All that said, Fuzzy Mud is still a very good book. As far as Sachar's work goes, however, it's not on the level of Holes or Sideways Stories from Wayside School, and as far as this year's crop of books goes, I don't think it reaches the heights of Circus Mirandus or Moonpenny Island (among others), and I don't expect it to take home the Newbery Medal.

Published in August by Delacorte / Random House

Monday, October 5, 2015

2016 Contenders: Dear Hank Williams, by Kimberly Willis Holt

The year is 1948 in the small town of Rippling Creek, Louisiana (which has several creeks, none of which are particularly rippling, come to think of it). Tate P. Ellerbee’s new teacher has assigned her students to strike up a correspondence with a pen pal. Tate knows exactly who she’ll write: her favorite singer, Hank Williams, whose music career is just kicking off with a regular gig on the Louisiana Hayride radio show. Tate tells Mr. Hank Williams about how she lives with her Aunt Patty Cake and her Uncle Jolly, how she wants a dog more than anything, and how she’s secretly practicing to sing in the Rippling Creek May Festival Talent Show and (hopefully beat that spoiled brat Verbia Calhoon).

I found several things about the novel quite interesting:

1. It’s historical fiction that really skirts around the edges of the era it’s portraying, rather than tackling it head on. WWII, which has just ended, is only mentioned tangentially, and Rippling Creek’s marginalized African American community is only touched upon. These two things alone could be the subjects of their own books, but Dear Hank Williams is about Tate, who is eleven years old, and her family, who aren’t really affected by those issues, so they become backdrop to the primary drama which is centered around school, and talent shows, and listening to the radio.

2. It takes place during a golden age of music that is dear to my heart: Radio Days. A time when, if you wanted to hear your favorite artist, you had to tune into the radio, maybe at a certain time, on a certain station. A time when procuring and owning a recorded piece of music was extremely special. A time when we had to physically interact with our music (turn the dial on the radio, put the needle on the record). A time when listening to music was a social event you experienced with your friends and family. A time when you could hear someone singing and never know, or care, what they looked like. Vinyl, and independent artists, are enjoying a bit of a resurgence lately, but for the most part all of this is just gone. You can own music as fast you can click “download.” You can easily push a button and listen to it on your headphones. You can know, and judge, what the artist looks like instantaneously. In fact, many people are given record contracts for seemingly no reason besides that their image is marketable! I wonder if the children who’ll read Dear Hank Williams will appreciate this. And I wonder too if they’ll be able to put Hank Williams, an old time country singer, with a proclivity for yodeling, into the context of his time period. Tate is basically writing a pop star. She is basically writing to Justin Bieber (but 2010 Justin Bieber who was kind of adorable, not 2015 Justin Bieber who is kind of ridiculous).

3. Tate is an unreliable narrator, but the untruths she tells are told with such sincerity you forgive and forget her unreliability. It’s quite an achievement on author Kimberly Willis Holt’s part to create a character so likable that you aren’t mad at her for lying, and despite her giving you a totally justifiable reason to mistrust her, you just don’t want to.

4. The book is written in the epistolary style, and is chock full of the folksy charm that seems to automatically accompany any novel set in a small town America, which readers have been known to either love or hate, with little gray area in between. I liked it, but, to quote my favorite bloggers, Sam and Rachael, “your mileage may vary.”

5. The book tackles some tough issues. Substance abuse, abandonment, and death are all explored as Tate journals her feelings in letters to Hank Williams. Her revelations are unexpected, but not unsurprising, and the serious themes are treated with the dignity they deserve.

I wouldn’t be surprised if this book gets attention from the Newbery committee. It can be hard for a group of opinionated librarians (and honorary librarians) to agree on what’s best. I feel Dear Hank Williams could be a unifying book with its many aspects worth celebrating.

For now, let’s channel Tate Ellerbee, and listen to some of that fine music by the late, legendary Hank Williams Sr.

I found several things about the novel quite interesting:

1. It’s historical fiction that really skirts around the edges of the era it’s portraying, rather than tackling it head on. WWII, which has just ended, is only mentioned tangentially, and Rippling Creek’s marginalized African American community is only touched upon. These two things alone could be the subjects of their own books, but Dear Hank Williams is about Tate, who is eleven years old, and her family, who aren’t really affected by those issues, so they become backdrop to the primary drama which is centered around school, and talent shows, and listening to the radio.

2. It takes place during a golden age of music that is dear to my heart: Radio Days. A time when, if you wanted to hear your favorite artist, you had to tune into the radio, maybe at a certain time, on a certain station. A time when procuring and owning a recorded piece of music was extremely special. A time when we had to physically interact with our music (turn the dial on the radio, put the needle on the record). A time when listening to music was a social event you experienced with your friends and family. A time when you could hear someone singing and never know, or care, what they looked like. Vinyl, and independent artists, are enjoying a bit of a resurgence lately, but for the most part all of this is just gone. You can own music as fast you can click “download.” You can easily push a button and listen to it on your headphones. You can know, and judge, what the artist looks like instantaneously. In fact, many people are given record contracts for seemingly no reason besides that their image is marketable! I wonder if the children who’ll read Dear Hank Williams will appreciate this. And I wonder too if they’ll be able to put Hank Williams, an old time country singer, with a proclivity for yodeling, into the context of his time period. Tate is basically writing a pop star. She is basically writing to Justin Bieber (but 2010 Justin Bieber who was kind of adorable, not 2015 Justin Bieber who is kind of ridiculous).

3. Tate is an unreliable narrator, but the untruths she tells are told with such sincerity you forgive and forget her unreliability. It’s quite an achievement on author Kimberly Willis Holt’s part to create a character so likable that you aren’t mad at her for lying, and despite her giving you a totally justifiable reason to mistrust her, you just don’t want to.

4. The book is written in the epistolary style, and is chock full of the folksy charm that seems to automatically accompany any novel set in a small town America, which readers have been known to either love or hate, with little gray area in between. I liked it, but, to quote my favorite bloggers, Sam and Rachael, “your mileage may vary.”

5. The book tackles some tough issues. Substance abuse, abandonment, and death are all explored as Tate journals her feelings in letters to Hank Williams. Her revelations are unexpected, but not unsurprising, and the serious themes are treated with the dignity they deserve.

I wouldn’t be surprised if this book gets attention from the Newbery committee. It can be hard for a group of opinionated librarians (and honorary librarians) to agree on what’s best. I feel Dear Hank Williams could be a unifying book with its many aspects worth celebrating.

For now, let’s channel Tate Ellerbee, and listen to some of that fine music by the late, legendary Hank Williams Sr.

Friday, October 2, 2015

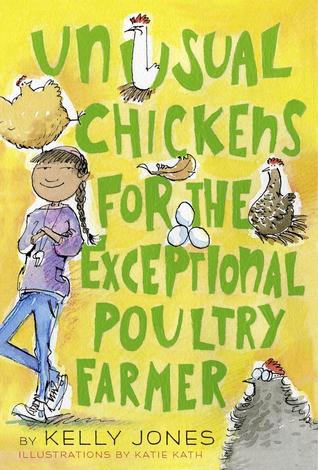

2016 Contenders: Unusual Chickens for the Exceptional Poultry Farmer, by Kelly Jones

I can't remember the last time I saw Daniel Pinkwater blurb a book. Of course, this one is not only about chickens (a special interest for Pinkwater) - it even name checks Pinkwater and his 1977 classic, The Hoboken Chicken Emergency. That has to be flattering. Still, Pinkwater is such a grouchy old coot that I have to believe he wouldn't praise a book unless he meant it. Of Unusual Chickens, he wrote, "Someone has finally written a real honest-to-goodness novel with chickens! This news will excite people who like novels, people who like chickens...and chickens. It is an unusual book!"

I can't remember the last time I saw Daniel Pinkwater blurb a book. Of course, this one is not only about chickens (a special interest for Pinkwater) - it even name checks Pinkwater and his 1977 classic, The Hoboken Chicken Emergency. That has to be flattering. Still, Pinkwater is such a grouchy old coot that I have to believe he wouldn't praise a book unless he meant it. Of Unusual Chickens, he wrote, "Someone has finally written a real honest-to-goodness novel with chickens! This news will excite people who like novels, people who like chickens...and chickens. It is an unusual book!"That it is. Sort of. On one level, the plot is a familiar one: a city girl moves to the country and struggles to fit in and make friends. In this case, the city girl, Sophie, and her mother are two of the only "brown people" in town (they are Latina), which only increases her feelings of alienation. They've left the city because Sophie's newly unemployed father has inherited a farm from his uncle, and along with it, several "unusual" chickens.

That's where the other side of the story comes in. The chickens are not unusual in the "Martha Stewart, tiny-pastel-egg-laying" sense, but more in the "turn raccoons into stone and levitate the chicken coop" sense. Clearly, their care calls for an exceptional poultry farmer. Sophie's quest to become that farmer parallels her inner journey as she adjusts to her new surroundings. Of course, since we are dealing with supernatural chickens, there are many absurd and comedic stops along the way.

First-time novelist Kelly Jones tells Sophie's story mostly through letters to her deceased grandmother, her great-uncle, and Agnes, the farmer who originally sold the unusual chickens. This farmer occasionally writes back, in letters whose erratic spelling and punctuation she blames on a malfunctioning typewriter (this may be a ruse - the unraveling of Agnes's mystery provides one of the more entertaining threads of this tale). The candid first-person narration allows Sophie's practical, wry, tween voice to shine through, and it is an appealing and authentic voice. There's a nice balance between supernatural comedy and real world concerns, and Katie Kath's line drawings play up the humor.

Unusual Chickens is a small gem of a book, written with a light touch and a sensitive heart. I'll be surprised if it doesn't show up on the Notable Books list, though it's probably a long shot for the Newbery.

Published in May 2015 by Knopf Books for Young Readers

Thursday, October 1, 2015

New Member of the For Those About to Mock Team: Tess Goldwasser

We've got an exciting announcement to make today! For the first time ever, For Those About to Mock is officially adding a new blog writer. Please join us in welcoming Tess Goldwasser to the For Those About to Mock team!

Longtime readers may recognize Tess's name, as she's already written five guest reviews for us. She's a ukulele queen, an octopus enthusiast, and a style icon. Tess is a Youth Services Librarian at the St. Mary's County Library in Maryland, and has an impressive history of professional service: she's served on the Stonewall Book Award Committee and the GLBTRT News Committee, and she is currently chairing the GLBTRT Advocacy Committee. She's a seasoned book blogger, having written for years over at Kid's Book Blog, and she's been one of our co-presenters at our annual Children's Literature: Best of the Year events for the past several years.

Basically, we can't say enough good things about Tess, and we're bouncing up and down with glee because she's joined the blog team.

Longtime readers may recognize Tess's name, as she's already written five guest reviews for us. She's a ukulele queen, an octopus enthusiast, and a style icon. Tess is a Youth Services Librarian at the St. Mary's County Library in Maryland, and has an impressive history of professional service: she's served on the Stonewall Book Award Committee and the GLBTRT News Committee, and she is currently chairing the GLBTRT Advocacy Committee. She's a seasoned book blogger, having written for years over at Kid's Book Blog, and she's been one of our co-presenters at our annual Children's Literature: Best of the Year events for the past several years.

Basically, we can't say enough good things about Tess, and we're bouncing up and down with glee because she's joined the blog team.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)