When last we left Jack Gantos (the character, not the author), the mystery of the murders of the Original Norvelters had been solved, his ever-bleeding nose had been repaired, and he'd even managed to talk some temporary sense into his father. However, once Jack's mother sends him on a trip to accompany the curmudgeonly Miss Volker to Eleanor Roosevelt's grave, everything rapidly deteriorates again. Jack and Miss Volker end up on a journey to Florida -- a journey filled with Classics Illustrated comic books, harpoons, and the vintage Gantos sense of an entire universe spiraling out of the control of a hapless, befuddled narrator.

The last book that Gantos (the author) wrote was, of course, Dead End in Norvelt, which took the 2012 Newbery. I actually think that Nowhere is a stronger book than Dead End -- it's funnier, more emotionally complex, and more thematically deep. There aren't too many sequels to Newbery books that manage to top the original, but I think Nowhere may well be one.

Paradoxically, I also think it's much less likely to win. The 2012 award year was, as we've mentioned before, a really odd one, and Dead End in Norvelt is very much an outlier in the Newbery canon. It's a humorous mystery that won an award that only infrequently goes to mysteries, and almost never goes to something funny. It also represented the longest time between an author's debut and winning the Newbery.

This was partly because the list of 2012 contenders wasn't very deep, and the titles that attracted the most attention were so divisive that it might have been impossible to build consensus around any of them (see: Okay for Now, Breadcrumbs, Junonia). I don't feel like that's the case this year, and I think that's what it would take for another Gantos novel that works in genres and styles that rarely show up in the Newbery to take home the medal.

Additionally, despite the fact that the Newbery criteria state quite clearly that each book is to be considered on its own, without reference to any of an author's other works, there's no precedent for two books in the same series winning the top prize. We've seen, within a series, one book win the Newbery and then another one honor (e.g., Dicey's Song [1983 winner] and A Solitary Blue [1984 honor]); a book take an honor and then another one win (The Dark is Rising [1974 honor] and The Grey King [1976 winner]; The Black Cauldron [1966 honor] and The High King [1969 winner]); and several books in the same series be given honors (all five of Laura Ingalls Wilder's honor titles); but never two winners from the same set. It's possible that someday, we'll see it happen, but I just don't see the Norvelt books as being the ones to break that barrier.

Anyone who enjoyed Dead End will likely also enjoy Nowhere, and I think it's an excellent novel. Just don't put all your money on it winning the Newbery.

Published in September by Farrar Straus Giroux / MacMillan

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

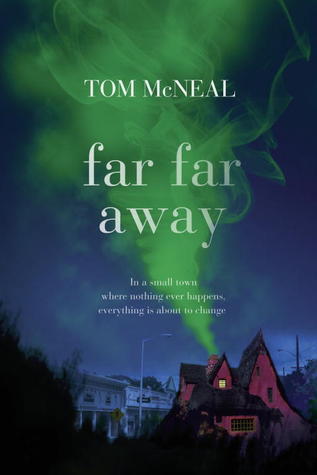

2014 Contenders: Far Far Away, by Tom McNeal

Far Far Away is the story, as the narrator tells us at the outset, of a boy, a girl, and a ghost. The ghost, who is also the narrator, happens to be the spirit of Jacob Grimm, one half of the famous Grimm brothers. The boy is clairaudient - able to hear spirits - and the girl is an ebullient mischief-maker. Their story, and the story of their fairy-tale-ish town, Never Better, would be an idyllic one, if it were not for one additional character: the sinister Finder of Occasions. It is also this character's presence that calls into question whether the book falls within the prescribed Newbery age grange. When he makes his move, the story grows very dark indeed.

Far Far Away is the story, as the narrator tells us at the outset, of a boy, a girl, and a ghost. The ghost, who is also the narrator, happens to be the spirit of Jacob Grimm, one half of the famous Grimm brothers. The boy is clairaudient - able to hear spirits - and the girl is an ebullient mischief-maker. Their story, and the story of their fairy-tale-ish town, Never Better, would be an idyllic one, if it were not for one additional character: the sinister Finder of Occasions. It is also this character's presence that calls into question whether the book falls within the prescribed Newbery age grange. When he makes his move, the story grows very dark indeed.What do the Newbery criteria have to say about age-appropriateness?

2. A “contribution to American literature for children” shall be a book for which children are an intended potential audience. The book displays respect for children’s understandings, abilities, and appreciations. Children are defined as persons of ages up to and including fourteen, and books for this entire age range are to be considered.

Many books fall obviously inside or outside the "up to and including fourteen" range. The Year of Billy Miller is in. Looking for Alaska is out (forgive the old example - I haven't read any YA this year, unless you count the title currently under discussion). Some books are more difficult to categorize. Age of protagonist can be a indicator, but not always - Hattie Ever After feels like a solid middle grade book, despite the fact that Hattie is seventeen or eighteen. Violence and/or sexual content can also catapult a book out of the Newbery range. If all else fails, you can fall back on a rule of thumb I think I first read on the child_lit listserv: a true children's book always ends on a hopeful note.

So how does Far Far Away measure up? Jeremy and Ginger, the main child characters, are fifteen - a little older than the Newbery range, but children do "read up." There's no sexual content more prurient than a chaste kiss on the lips. And the violence, while present, is more suggestive than graphic. Finally, the ending is categorically happy and hopeful, as befits the fairy tale structure.

BUT.

For its last third, just before the happy ending, the book turns into a true horror novel. There's no bloodshed or brute violence, but things grow uncomfortably dark. Darker than we imagine our Newbery books to be. As dark as real life can get, in fact.

At first that section made me say, "Welp, definitely not a Newbery contender!" And obviously, I won't be handing it to my seven-year-old. But I thought back to what I was reading when I was thirteen and fourteen, and you know what? Those were the years when I discovered Stephen King. I was reading The Shining, Misery, Carrie, etc. And I wasn't the only one. We were also passing around Flowers in the Attic in those days, and whatever V.C. Andrews lacked in literary quality she definitely made up for in pure creepiness. And, heck, in school we were reading Guy de Maupassant and Poe. For all their historical distance, those guys still pack a creepy punch.

Can we really say that Far Far Away is less appropriate for fourteen-year-olds than Maupassant and Poe? When we're supposed to be considering books for the entire age range?

I have a feeling that Far Far Away will make people too uncomfortable to get any Newbery love, but I would argue that it does fall within the Newbery range. And yes, by the way, it is distinguished - in character, in setting, in theme, in style, but probably most of all in plot. I can't think of another book this year that so effectively and methodically tightened the suspense noose. And when the trap was finally sprung, the payoff was dark - yes - but deliciously effective.

Published in June by Knopf Books for Young Readers

Monday, October 28, 2013

2014 Contenders: Africa is My Home, by Monica Edinger

Full disclosure: the About to Mock ranch is very much a Monica Edinger fan club. We love her blog (if by some odd chance, you read us and not her, you should rectify that immediately), we eagerly devour her reviews in The Horn Book and The New York Times, and we're very grateful for her support in our own book discussion endeavors. We think she's awesome, and so I can't help but have that in my mind as I'm reading her work.

Africa is My Home is the fictionalized story of Sarah Margru Kinson, one of a handful of children who happened to be aboard the slave ship Amistad, of Supreme Court and Steven Spielberg fame. It follows her from her childhood in what is now Sierra Leone, through her experiences aboard the ship and in America, and on into her adult life. It's a fascinating read that sheds light on a little-known part of a famous story.

Indeed, though Africa is My Home is a short, heavily illustrated book with a single narrator, the book I was reminded of while reading it was No Crystal Stair. Both books discuss lesser-known figures involved in famous events, and interestingly, in both cases, the author attempted to write the book as straight nonfiction first before realizing that the paucity of firsthand data made that impossible.

I think Africa is the better of the two books, partly because it maintains its focus so well (which was my complaint about No Crystal Stair, though I was really the only one complaining, so take that for what it's worth). But Africa also breaks into poetry occasionally -- poetry that truly sings. Those passages are, in my opinion, the best part of the book, to the point that what I really want now is to read a book of Edinger's poetry. I'd put good money on it being awesome.

The one quibble I had with the book has to do with its being narrated in the first person by Sarah -- but a version of Sarah who is fully grown and looking back on the events of the narrative. This allows for the inclusion of facts and interpretations of events that a child wouldn't necessarily know or comprehend, but I felt like that temporal distance made the book lose some emotional immediacy. It's not a huge issue, but especially given that there's no such emotional gap in the poetic bits, it was something I noticed.

Although it can't be taken into account for Newbery purposes, this is also a truly beautiful-looking book. The illustrations are by Robert Byrd (Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!, Electric Ben), who captures the feel of 19th-century broadsides and maps while still imparting his signature style. It's a great pairing with the text, and the editors of the book should be commended for that.

The Newbery committee historically is very unfriendly to "picture books" -- even comparatively long ones with lots of text -- and if Africa were somehow to win, I think it might be the shortest winner since maybe Sarah, Plain and Tall (1986). That doesn't feel likely to me this year, but if Africa doesn't make the notables list, you'll definitely be able to color me surprised.*

*As a side note, it's worth noting that, although Byrd has illustrated both a Newbery winner and a Prinz honor book, he's never received any Caldecott love. I'm categorically not a Caldecott expert, but I'd really like to see Byrd recognized there.

Published in October by Candlewick

Africa is My Home is the fictionalized story of Sarah Margru Kinson, one of a handful of children who happened to be aboard the slave ship Amistad, of Supreme Court and Steven Spielberg fame. It follows her from her childhood in what is now Sierra Leone, through her experiences aboard the ship and in America, and on into her adult life. It's a fascinating read that sheds light on a little-known part of a famous story.

Indeed, though Africa is My Home is a short, heavily illustrated book with a single narrator, the book I was reminded of while reading it was No Crystal Stair. Both books discuss lesser-known figures involved in famous events, and interestingly, in both cases, the author attempted to write the book as straight nonfiction first before realizing that the paucity of firsthand data made that impossible.

I think Africa is the better of the two books, partly because it maintains its focus so well (which was my complaint about No Crystal Stair, though I was really the only one complaining, so take that for what it's worth). But Africa also breaks into poetry occasionally -- poetry that truly sings. Those passages are, in my opinion, the best part of the book, to the point that what I really want now is to read a book of Edinger's poetry. I'd put good money on it being awesome.

The one quibble I had with the book has to do with its being narrated in the first person by Sarah -- but a version of Sarah who is fully grown and looking back on the events of the narrative. This allows for the inclusion of facts and interpretations of events that a child wouldn't necessarily know or comprehend, but I felt like that temporal distance made the book lose some emotional immediacy. It's not a huge issue, but especially given that there's no such emotional gap in the poetic bits, it was something I noticed.

Although it can't be taken into account for Newbery purposes, this is also a truly beautiful-looking book. The illustrations are by Robert Byrd (Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!, Electric Ben), who captures the feel of 19th-century broadsides and maps while still imparting his signature style. It's a great pairing with the text, and the editors of the book should be commended for that.

The Newbery committee historically is very unfriendly to "picture books" -- even comparatively long ones with lots of text -- and if Africa were somehow to win, I think it might be the shortest winner since maybe Sarah, Plain and Tall (1986). That doesn't feel likely to me this year, but if Africa doesn't make the notables list, you'll definitely be able to color me surprised.*

*As a side note, it's worth noting that, although Byrd has illustrated both a Newbery winner and a Prinz honor book, he's never received any Caldecott love. I'm categorically not a Caldecott expert, but I'd really like to see Byrd recognized there.

Published in October by Candlewick

2014 Second Takes: Zebra Forest, by Adina Rishe Gewirtz

Sam would probably make a better Newbery committee member than I would, at least in one sense. He's much better than I am at watching for the outliers - the books that aren't getting as much buzz, the debut novels, etc. I don't always agree with his assessment of them, but sometimes he uncovers a gem like Zebra Forest, which did receive one starred review, but which is otherwise flying somewhat under the radar.

I think it deserves more attention, and whether you will agree with me will depend heavily on whether you think the twist is a heavy-handed coincidence or shrewd piece of plotting.

Ok. I'll put this behind a big caps-locked SPOILER, even though the twist comes in chapter 7 (out of 39).

I think it was a deliberate choice and not all coincidence that Annie, Rew, and Gran were living just across the zebra forest from the prison where Andrew Snow (Annie and Rew's father; Gran's son) was incarcerated. It's completely in character for Gran to have stopped visiting her son, disappeared from her last known address, and then, in order to make some sort of symbolic amends, to keep vigil almost within sight of his prison cell. This is a book filled with conflicted characters who are constantly cutting off their noses to spite their own faces.

They're also some of the most interesting characters I've encountered in middle grade fiction this year. Middle grade books are full of broken families and unsuitable guardians, but in this case I believed in them. Gran is about the same age as my own grandparents, and I recognized the habits of that generation in her. Her struggles with mental illness also rang true, as did the coping strategies of the two children.

Plot-wise, I was surprised by the author's choice to front-load all of the major action. As I said, the big reveal comes not even 25% of the way through the book, which means that the reader's interest must then be sustained, somehow, for the next 150+ pages. As the tension of the hostage situation gradually gives way to the revelation of family secrets, the pacing never seems to drag.

And then, of course, there's the setting - the isolated house, the forest that's almost a character in its own right, and the very specific and carefully chosen historical moment (during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1980). These are all vividly drawn, and help to underscore the themes of moral choices and the way secrets hold us prisoner.

Not bad, Zebra Forest. Not bad at all.

I think it deserves more attention, and whether you will agree with me will depend heavily on whether you think the twist is a heavy-handed coincidence or shrewd piece of plotting.

Ok. I'll put this behind a big caps-locked SPOILER, even though the twist comes in chapter 7 (out of 39).

I think it was a deliberate choice and not all coincidence that Annie, Rew, and Gran were living just across the zebra forest from the prison where Andrew Snow (Annie and Rew's father; Gran's son) was incarcerated. It's completely in character for Gran to have stopped visiting her son, disappeared from her last known address, and then, in order to make some sort of symbolic amends, to keep vigil almost within sight of his prison cell. This is a book filled with conflicted characters who are constantly cutting off their noses to spite their own faces.

They're also some of the most interesting characters I've encountered in middle grade fiction this year. Middle grade books are full of broken families and unsuitable guardians, but in this case I believed in them. Gran is about the same age as my own grandparents, and I recognized the habits of that generation in her. Her struggles with mental illness also rang true, as did the coping strategies of the two children.

Plot-wise, I was surprised by the author's choice to front-load all of the major action. As I said, the big reveal comes not even 25% of the way through the book, which means that the reader's interest must then be sustained, somehow, for the next 150+ pages. As the tension of the hostage situation gradually gives way to the revelation of family secrets, the pacing never seems to drag.

And then, of course, there's the setting - the isolated house, the forest that's almost a character in its own right, and the very specific and carefully chosen historical moment (during the Iranian hostage crisis in 1980). These are all vividly drawn, and help to underscore the themes of moral choices and the way secrets hold us prisoner.

Not bad, Zebra Forest. Not bad at all.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

2014 Second Takes: The Thing About Luck, by Cynthia Kadohata

"Some kids I knew would read only books that were about something they could relate to. But I was interested in other stuff."

When I got to that passage, I actually had to take a break from reading The Thing AboutCombines Luck to ponder the critical question: did I just get trolled by Cynthia Kadohata?

The book that prompts that statement from Summer, The Thing About Luck's protagonist, is A Separate Peace. A few paragraphs down, Summer muses further about that novel: "Why would a book in which hardly anything happened for most of the time eat at me so much? It was the weirdest thing."

I almost wonder if that isn't less character dialogue, and more Kadohata's artistic statement of intent. The Thing About Luck is a book in which hardly anything happens for most of the time, about a lifestyle that for most people is very remote, interrupted repeatedly with pages of technical and logistical details that don't advance what little plot there is. It's a book that aspires to make something powerful happen quietly, but unlike some other novels with similar aspirations (The Hidden Summer is probably the best example from this year), it doesn't pull together the elements well enough to make the power visible.

Many readers seem to be big fans of the characters, but I feel like Luck suffers from what the Onion AV Club calls "the hole in the middle." Summer's grandparents are wonderful and deep, and Mick, one of the Irish workers, reveals hidden sides to his personality as the novel progresses, but Summer herself is both frustratingly bland, and armed with a backstory (malaria!) that never really has a payoff. Jaz, Summer's brother, also feels like a blurry photocopy of characters we've encountered before. Again, I couldn't help but compare Luck unfavorably to The Hidden Summer, which gave shading and nuance to all of its characters, major and minor.

The vast emptiness of the mid-American setting is well-realized, even distinguished, to use the Newbery word. But Luck's plot is vapor-thin, and its prose is fine but unspectacular, and I think its style, with its constant interruptions of its own narrative, doesn't, in the end, succeed. It's not that I can't relate to it, I don't think, or that hardly anything happens (which also describes Breathing Room, and The Hidden Summer, and most of my favorite adult fiction) -- it's that the parts just don't add up to the whole that they aim to produce.

When I got to that passage, I actually had to take a break from reading The Thing About

The book that prompts that statement from Summer, The Thing About Luck's protagonist, is A Separate Peace. A few paragraphs down, Summer muses further about that novel: "Why would a book in which hardly anything happened for most of the time eat at me so much? It was the weirdest thing."

I almost wonder if that isn't less character dialogue, and more Kadohata's artistic statement of intent. The Thing About Luck is a book in which hardly anything happens for most of the time, about a lifestyle that for most people is very remote, interrupted repeatedly with pages of technical and logistical details that don't advance what little plot there is. It's a book that aspires to make something powerful happen quietly, but unlike some other novels with similar aspirations (The Hidden Summer is probably the best example from this year), it doesn't pull together the elements well enough to make the power visible.

Many readers seem to be big fans of the characters, but I feel like Luck suffers from what the Onion AV Club calls "the hole in the middle." Summer's grandparents are wonderful and deep, and Mick, one of the Irish workers, reveals hidden sides to his personality as the novel progresses, but Summer herself is both frustratingly bland, and armed with a backstory (malaria!) that never really has a payoff. Jaz, Summer's brother, also feels like a blurry photocopy of characters we've encountered before. Again, I couldn't help but compare Luck unfavorably to The Hidden Summer, which gave shading and nuance to all of its characters, major and minor.

The vast emptiness of the mid-American setting is well-realized, even distinguished, to use the Newbery word. But Luck's plot is vapor-thin, and its prose is fine but unspectacular, and I think its style, with its constant interruptions of its own narrative, doesn't, in the end, succeed. It's not that I can't relate to it, I don't think, or that hardly anything happens (which also describes Breathing Room, and The Hidden Summer, and most of my favorite adult fiction) -- it's that the parts just don't add up to the whole that they aim to produce.

Wednesday, October 16, 2013

2014 Second Takes: The Water Castle, by Megan Frazer Blakemore

I was looking forward to reading The Water Castle more than any other title on Sam's list. I am all about spooky old houses and baroque, intertwining plots. The intersection of fantasy, mystery, and science fiction is also an exciting place for me as a reader.

Sigh.

I'm afraid I'm with Nina Lindsay here. I just can't see any distinguished elements in this book.

Sam extolled the character development, but I disagree. The three main characters - Ephraim, Mallory, and Will - are reasonably well-developed, but they certainly don't measure up well beside Delphine of P.S. Be Eleven, Oscar of The Real Boy, or Billy Miller. The secondary characters, on the other hand, are either vague outlines (Ephraim's mother, Brynn, Mallory's dad) or caricatures meant to advance the plot (Price, Will's dad, Orlando Appledore). I agree with whoever said that Price seems to exist only to provide a foil for Ephraim's immaturity and ineptitude. Ditto Winifred Wylie, who's a total Nellie Oleson, and a foil for Nora.

I can't find a lot to admire in the plot either. The multiple threads are handled clumsily, and a lot of the events feel forced. I was particularly disappointed in the sudden resolution of the conflict among Ephraim, Mallory, and Will. One minute they're enemies, and the next they're friends, and this is brought about by... what? A walk down a tunnel? That's a failing of both character and plot, actually.

Sam also admired the ambiguous ending, and the way the author doesn't spell out the solutions to the various mysteries. I actually agree with him on that, but it feels disingenuous after the reader has been bashed with the foreshadowing stick for the preceding 275 pages. You can't give a Dickens novel a Virginia Woolf ending. Or you can, I guess, but it makes for a jarring reading experience.

Some of the prose is well-crafted, stylistically, but that's not enough to save The Water Castle for me.

Sigh.

I'm afraid I'm with Nina Lindsay here. I just can't see any distinguished elements in this book.

Sam extolled the character development, but I disagree. The three main characters - Ephraim, Mallory, and Will - are reasonably well-developed, but they certainly don't measure up well beside Delphine of P.S. Be Eleven, Oscar of The Real Boy, or Billy Miller. The secondary characters, on the other hand, are either vague outlines (Ephraim's mother, Brynn, Mallory's dad) or caricatures meant to advance the plot (Price, Will's dad, Orlando Appledore). I agree with whoever said that Price seems to exist only to provide a foil for Ephraim's immaturity and ineptitude. Ditto Winifred Wylie, who's a total Nellie Oleson, and a foil for Nora.

I can't find a lot to admire in the plot either. The multiple threads are handled clumsily, and a lot of the events feel forced. I was particularly disappointed in the sudden resolution of the conflict among Ephraim, Mallory, and Will. One minute they're enemies, and the next they're friends, and this is brought about by... what? A walk down a tunnel? That's a failing of both character and plot, actually.

Sam also admired the ambiguous ending, and the way the author doesn't spell out the solutions to the various mysteries. I actually agree with him on that, but it feels disingenuous after the reader has been bashed with the foreshadowing stick for the preceding 275 pages. You can't give a Dickens novel a Virginia Woolf ending. Or you can, I guess, but it makes for a jarring reading experience.

Some of the prose is well-crafted, stylistically, but that's not enough to save The Water Castle for me.

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

2014 Second Takes: The Year of Billy Miller, by Kevin Henkes

The Year of Billy Miller is a Kevin Henkes novel.

I feel like I can almost stop writing there. Henkes has notable strengths -- the uncanny feel for his child characters' thoughts and emotions, the simple and understated prose -- and they're in full effect here. If you like Kevin Henkes, any Kevin Henkes, you'll almost certainly enjoy Billy Miller.

However, I'm not sure how I feel about Billy Miller in the Newbery discussion. It's distinguished in characters, certainly, and it also has a lovely style. If you want to think about accurately portraying the thoughts and feelings of real people as "presentation of information," I'd give you that one too. It's a strong book, no question about it.

On the other hand, the setting doesn't come into particularly sharp focus; when at one point, Billy and his friend Ned mention the possibility of getting lost and walking all the way to Lake Michigan, I have to confess that I'd essentially forgotten that the book was set in Wisconsin. The argument could be made that it's the portions of the setting that are most relevant to a child that are most carefully delineated, such as Billy's home and school, but compared to many of this year's other strong contenders, I just don't think it's particularly noteworthy.

Maybe more importantly, the plot is loose at best. Billy Miller is episodic by design, and that's not in and of itself a problem, but I feel like the connections between the parts just aren't all that strong. Even within the sections, there's sometimes a weakness in construction. In the last part, for instance, Billy makes a special effort to surreptitiously take a pearl, which he had previously given to his sister Sal, from the box underneath her bed where she keeps it. He hopes that it will bring him luck at his poetry reading, and notes that he'll return it after the show. This sounds like the setup to a conflict -- but, aside from one line about Billy rubbing the pearl for good luck on his way up to the microphone, it's never mentioned again. This isn't the only thread that's discarded without having much of a payoff, and I don't think it helps Henkes' cause.

These are, to some extent, quibbles -- The Year of Billy Miller is, overall, very good, as one would expect from Henkes. But at this time of year, we're trying to zero in on the best of the best, and so quibbles become magnified in importance. As much as we all admire The Henk around here, I think Billy Miller doesn't quite reach the top tier of this year's Newbery candidates.

I feel like I can almost stop writing there. Henkes has notable strengths -- the uncanny feel for his child characters' thoughts and emotions, the simple and understated prose -- and they're in full effect here. If you like Kevin Henkes, any Kevin Henkes, you'll almost certainly enjoy Billy Miller.

However, I'm not sure how I feel about Billy Miller in the Newbery discussion. It's distinguished in characters, certainly, and it also has a lovely style. If you want to think about accurately portraying the thoughts and feelings of real people as "presentation of information," I'd give you that one too. It's a strong book, no question about it.

On the other hand, the setting doesn't come into particularly sharp focus; when at one point, Billy and his friend Ned mention the possibility of getting lost and walking all the way to Lake Michigan, I have to confess that I'd essentially forgotten that the book was set in Wisconsin. The argument could be made that it's the portions of the setting that are most relevant to a child that are most carefully delineated, such as Billy's home and school, but compared to many of this year's other strong contenders, I just don't think it's particularly noteworthy.

Maybe more importantly, the plot is loose at best. Billy Miller is episodic by design, and that's not in and of itself a problem, but I feel like the connections between the parts just aren't all that strong. Even within the sections, there's sometimes a weakness in construction. In the last part, for instance, Billy makes a special effort to surreptitiously take a pearl, which he had previously given to his sister Sal, from the box underneath her bed where she keeps it. He hopes that it will bring him luck at his poetry reading, and notes that he'll return it after the show. This sounds like the setup to a conflict -- but, aside from one line about Billy rubbing the pearl for good luck on his way up to the microphone, it's never mentioned again. This isn't the only thread that's discarded without having much of a payoff, and I don't think it helps Henkes' cause.

These are, to some extent, quibbles -- The Year of Billy Miller is, overall, very good, as one would expect from Henkes. But at this time of year, we're trying to zero in on the best of the best, and so quibbles become magnified in importance. As much as we all admire The Henk around here, I think Billy Miller doesn't quite reach the top tier of this year's Newbery candidates.

Wednesday, October 9, 2013

2014 Contenders: Twerp, by Mark Goldblatt

Aren't we supposed to be doing our Second Takes right now, you ask? Why yes, yes we are. But I already had this one on my desk, and now that I've finished reading it, I can't help but want to talk about it.

I have to confess that it took me a long time to get around to reading Twerp. We got an ARC of it ages ago, but neither Rachael nor I felt very enthusiastic about reading it. It wasn't until About To Mock reader Destinee tweeted to us that we should take a look at it that I retrieved it from the shelf, and it wasn't until I'd carried it around in my bag for three weeks or so that I even cracked the cover.

I think part of my reticence was that the language on the back cover of the ARC frames the novel as an anti-bullying message novel. My tepid feelings about Wonder weren't really a secret, and yet that was still one of the best books of its type that I've seen. This didn't seem like all that promising of a haystack to go needle-searching in.

Who knows, maybe the anti-bullying marketing will be successful in bringing Twerp some extra sales. However, the novel is much more complex than that. It's a detailed snapshot of New York City in the 1960s, a thoughtful examination of the awkwardness and fitfulness of first crushes, and an incisive look at what makes otherwise good people do terrible things. Although bullying certainly is a key theme, it's not even close to the only thing going on in the book.

I found the characters believable, especially Julian Twerski, the book's narrator. Also highly effective is the book's structure; it's set up as a lengthy writing assignment that Julian is doing for his sixth-grade English teacher. His teacher wants him to talk about the bullying incident that Julian was involved in, but Julian isn't that keen to discuss it. As a result, the book circles around and around, coming always closer, but never quite hitting the central plot point until the very end of the novel. It's an excellent way to keep the suspense up, and it doesn't -- to me at least -- feel inauthentic.

The end result is a surprisingly strong novel that deals honestly and truthfully with moral complications. Is it better than The Real Boy or Zebra Forest? I don't think it quite is, but it's very solidly in the next tier, and it's definitely worth consideration.

Published in May by Random House.

I have to confess that it took me a long time to get around to reading Twerp. We got an ARC of it ages ago, but neither Rachael nor I felt very enthusiastic about reading it. It wasn't until About To Mock reader Destinee tweeted to us that we should take a look at it that I retrieved it from the shelf, and it wasn't until I'd carried it around in my bag for three weeks or so that I even cracked the cover.

I think part of my reticence was that the language on the back cover of the ARC frames the novel as an anti-bullying message novel. My tepid feelings about Wonder weren't really a secret, and yet that was still one of the best books of its type that I've seen. This didn't seem like all that promising of a haystack to go needle-searching in.

Who knows, maybe the anti-bullying marketing will be successful in bringing Twerp some extra sales. However, the novel is much more complex than that. It's a detailed snapshot of New York City in the 1960s, a thoughtful examination of the awkwardness and fitfulness of first crushes, and an incisive look at what makes otherwise good people do terrible things. Although bullying certainly is a key theme, it's not even close to the only thing going on in the book.

I found the characters believable, especially Julian Twerski, the book's narrator. Also highly effective is the book's structure; it's set up as a lengthy writing assignment that Julian is doing for his sixth-grade English teacher. His teacher wants him to talk about the bullying incident that Julian was involved in, but Julian isn't that keen to discuss it. As a result, the book circles around and around, coming always closer, but never quite hitting the central plot point until the very end of the novel. It's an excellent way to keep the suspense up, and it doesn't -- to me at least -- feel inauthentic.

The end result is a surprisingly strong novel that deals honestly and truthfully with moral complications. Is it better than The Real Boy or Zebra Forest? I don't think it quite is, but it's very solidly in the next tier, and it's definitely worth consideration.

Published in May by Random House.

Monday, October 7, 2013

2014 Second Takes: Navigating Early

I was in the "Moon over what?!" group when Clare Vanderpool's Newbery win was announced. I immediately sought out out and read Moon Over Manifest and... well... I didn't agree with Sam Bloom.* It was good, but not Newbery good.

Then Sam (Eddington) read her follow-up, Navigating Early. He didn't like it. When he described the plot to me, it sounded ludicrous, but other people seemed to like it, so I put it on my "give it a chance" list. And finally, I did.

In the grand Cooperative Children's Book Center tradition, I'll start with the good.

Vanderpool does setting really well here, better than she did in Manifest, I think, and setting was one of the strongest aspects of that book. She captures both the boarding school and the deep woods of Maine effectively, and even gives a sense, in flashback, of the wide vistas of the Kansas prairie.

The side plots are intriguing as well - all of the people that Jack and Early meet in the woods, and the ways their stories entwine. The dream-like nature of those encounters, and the way they advance the plot and the theme, reminded me of Breadcrumbs.

In terms of integrating what I'll call the Pi Story Plot with the realistic plot though, I think Vanderpool fails where Ursu succeeded. It's just not made clear, either explicitly or implicitly, how the reader is meant to categorize that whole story. Is Early clairvoyant, reading the actual future in the (erroneous, but that's another story) numbers of pi? Is magic at work? Nothing about the tone of the rest of the story suggests that we should take it as magical realism. It's just confusing. Narrator Jack tells us that his mother used to say that "There are no coincidences. Just boatloads of miracles." Are we supposed to take that at face value? I think a series of miracles makes for some weak plot scaffolding.

I'm also troubled by Early as a character. In the way his disability advances the plot and brings about a revelation for the non-disabled character, he felt a bit like a one-dimensional Magical Disabled Person to me (especially in contrast to Oscar from The Real Boy, whose disability is just one facet of his identity). I really, really hated the way he formed an instant rapport with everybody they met, like some kind of autistic Pollyanna.

Finally, there are a few too many instances where Vanderpool drives home her point by telling instead of showing. After the encounter between Jack and Mrs. Johanssen, he asks himself, "But how had her words meant so much to me, when she was speaking them to the son she thought had returned? Because she let me hear them as if they were being spoken to me. And I guess, in a way I let her speak to me as if I were her son." Revelations are not so effective when you have to spell them out.

In the end, I was left feeling the same frustration I felt after reading Moon Over Manifest: Navigating Early is almost a great book, but it never quite comes together.

*Known affectionately around the About to Mock ranch as "Sam Over Manifest". We'd still love to sit down over drinks sometime and pick his brain about that book.

Then Sam (Eddington) read her follow-up, Navigating Early. He didn't like it. When he described the plot to me, it sounded ludicrous, but other people seemed to like it, so I put it on my "give it a chance" list. And finally, I did.

In the grand Cooperative Children's Book Center tradition, I'll start with the good.

Vanderpool does setting really well here, better than she did in Manifest, I think, and setting was one of the strongest aspects of that book. She captures both the boarding school and the deep woods of Maine effectively, and even gives a sense, in flashback, of the wide vistas of the Kansas prairie.

The side plots are intriguing as well - all of the people that Jack and Early meet in the woods, and the ways their stories entwine. The dream-like nature of those encounters, and the way they advance the plot and the theme, reminded me of Breadcrumbs.

In terms of integrating what I'll call the Pi Story Plot with the realistic plot though, I think Vanderpool fails where Ursu succeeded. It's just not made clear, either explicitly or implicitly, how the reader is meant to categorize that whole story. Is Early clairvoyant, reading the actual future in the (erroneous, but that's another story) numbers of pi? Is magic at work? Nothing about the tone of the rest of the story suggests that we should take it as magical realism. It's just confusing. Narrator Jack tells us that his mother used to say that "There are no coincidences. Just boatloads of miracles." Are we supposed to take that at face value? I think a series of miracles makes for some weak plot scaffolding.

I'm also troubled by Early as a character. In the way his disability advances the plot and brings about a revelation for the non-disabled character, he felt a bit like a one-dimensional Magical Disabled Person to me (especially in contrast to Oscar from The Real Boy, whose disability is just one facet of his identity). I really, really hated the way he formed an instant rapport with everybody they met, like some kind of autistic Pollyanna.

Finally, there are a few too many instances where Vanderpool drives home her point by telling instead of showing. After the encounter between Jack and Mrs. Johanssen, he asks himself, "But how had her words meant so much to me, when she was speaking them to the son she thought had returned? Because she let me hear them as if they were being spoken to me. And I guess, in a way I let her speak to me as if I were her son." Revelations are not so effective when you have to spell them out.

In the end, I was left feeling the same frustration I felt after reading Moon Over Manifest: Navigating Early is almost a great book, but it never quite comes together.

*Known affectionately around the About to Mock ranch as "Sam Over Manifest". We'd still love to sit down over drinks sometime and pick his brain about that book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)