1. talks to a plant, and says it's her best friend

2. loves the dictionary, and peppers her story with

definitions

3. tragic past

Sam Eddington: crappy characters in kids' books?

Rachael Stein: YOU ARE A WINNER

I wanted to hate this book so much. I've read a lot of middle grade fiction these past few years, and if there's anything I hate more than folksiness that rings false, it's a Quirky Character. They always have tragic pasts, odd habits, and some kind of obsession that allows the author to frame the story in terms of word definitions, or household hints, or whatever. They always make me picture the author sitting in a writer's workshop, slaving away over a character sheet.

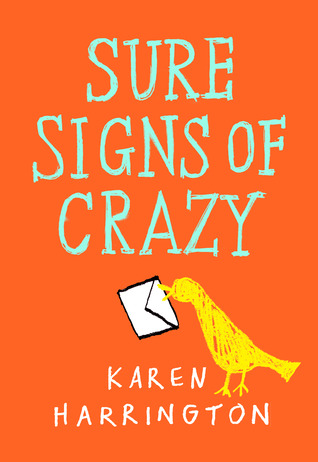

Sarah, the twelve-year-old protagonista of Sure Signs of Crazy, is Quirky all right. Tragic past? Mother tried to drown her in the sink when she was two, and succeeded in drowning her twin brother. Also, her father drinks a lot of Jim Beam. Odd habits? Talking to a plant and writing letters to Atticus Finch. Obsession? The dictionary. She keeps a list of what she calls "trouble words" - words that "will change the face of the person you say it to." A few pages in, I couldn't see this story going anywhere good.

I stuck with it though, and it didn't even take very long to win me over. I still think some of the Quirks should have stayed behind on the character sheet (though I was kind of attached to Plant by the end), but as artificial as she should seem, Sarah's voice is strong and genuine. Her words and her actions ring true, and she makes enough cringe-worthy mistakes to balance out her unusually perceptive letters to Atticus. Every one of the secondary characters is written gracefully as well. I hate when authors fail to respect their own characters, but Harrington writes with sympathy about even the least likeable members of her dramatis personae. That counts for a lot with me.

The settings are well-realized too. Living in a rental home myself, though not one as bleak as Sarah's, I recognize her descriptions of their less charming aspects (especially the cabinets). When she stands on the stump in her front yard and watches over her small town Texas neighborhood, I can see it clearly too, and she almost makes me like it.

Sure Signs of Crazy is getting a fair bit of attention, and it's certainly the type of book we think of as a "Newbery book" - missing mother, quirky girl (though not that many of the winners actually fit that profile). Depending on the committee's tastes, I can see it getting quite a few nominations for its distinguished characters and settings, and I wouldn't be surprised to see a silver Honor sticker on the cover next January.

Published in August by Little, Brown